Key Question: How can we design filesystems to store and manipulate files on disk?

- Linux and C libraries for file manipulation:

stat, struct stat, open, close, read, write, readdir, struct dirent, file descriptors, regular files, directories, soft and hard links, programmatic manipulation of them, implementation of ls, cp, cat, etc.

- naming, abstraction and layering concepts in systems as a means for managing complexity, blocks,

inodes, inode pointer structure, inode as abstraction over blocks, direct blocks, indirect blocks, doubly indirect blocks, design and implementation of a file system.

- additional systems examples that rely on naming, abstraction, modularity, and layering, including DNS, TCP/IP, network packets, databases, HTTP, REST, descriptors and **

pid**s.

- building modular systems with simultaneous goals of simplicity of implementation, fault tolerance, and flexibility of interactions.

Filesystem Design

Case Study: Unix V6 Filesystem

Using the Unix Version 6 Filesystem to see an example of filesystem design.

Files

Data Storage and Access

The stack, heap and other segments of program data live in memory (RAM)

- fast

- byte-addressable: can quickly access any byte of data by address, but not individual bits by address

- not persistent - cannot store data between power-offs

The filesystem lives on disk (eg. hard drives)

- slower

- persistent - stores data between power-offs

- sector-addressable: cannot read/write just one byte of data - can only read/write “sectors” of data

Filesystem goals

Case Study: The Unix v6 Filesystem

Sectors and Blocks

A filesystem generally defines its own unit of data, a “block,” that it reads/writes at a time.

- “Sector” = hard disk storage unit

- “Block” = filesystem storage unit (1 or more sectors) - software abstraction

The Unix V6 Filesystem defines a block to be 1 sector (so they are interchangeable).

Storing Data on Disk

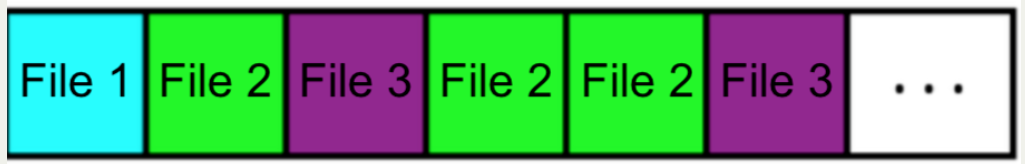

Two types of data we will be working with:

- file payload data - contents of files (e.g. text in documents, pixels in images)

- file metadata - information about files (e.g. name, size)

Key insight: both of these must be stored on the hard disk. his means some blocks must store metadata other than payload data.

-

Small files (less than 512 bytes) reserve entire block.

-

For files spanning multiple blocks, their blocks no to be adjacent.

-

We need somewhere to store information about each file, such as which block numbers store its payload data. Ideally, this data would be easy to look up as needed.

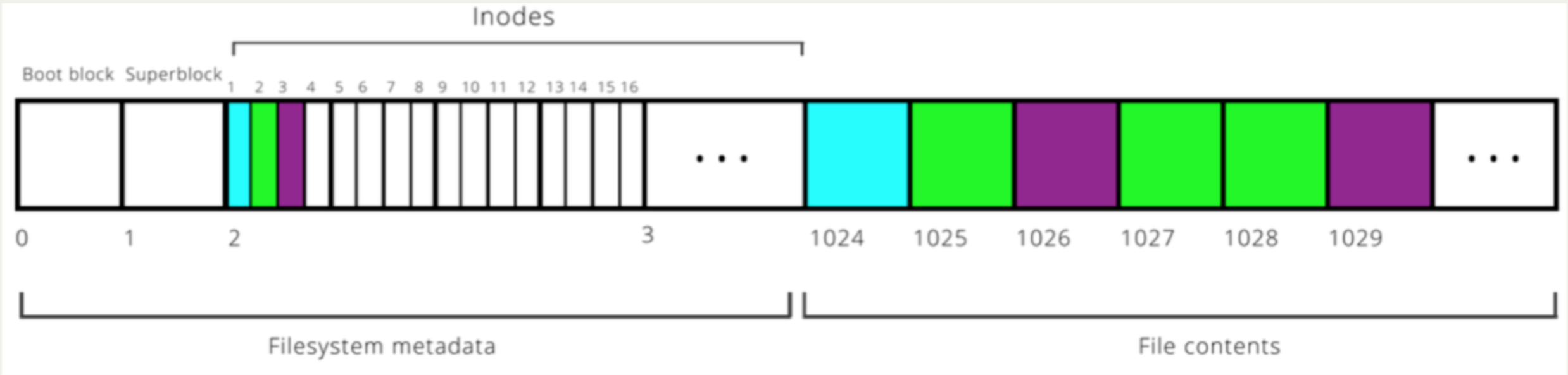

Inodes

An inode (“index node”) is a grouping of data about a single file. It stores things like:

- file size

- ordered list of block numbers that store file payload data

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

struct inode {

uint16_t i_mode; // bit vector of file

// type and permissions

uint8_t i_nlink; // number of references

// to file

uint8_t i_uid; // owner

uint8_t i_gid; // group of owner

uint8_t i_size0; // most significant byte

// of size

uint16_t i_size1; // lower two bytes of size

// (size is encoded in a

// three-byte number)

uint16_t i_addr[8]; // device addresses

// constituting file

uint16_t i_atime[2]; // access time

uint16_t i_mtime[2]; // modify time

};

|

An inode is 32 bytes big in this filesystem.

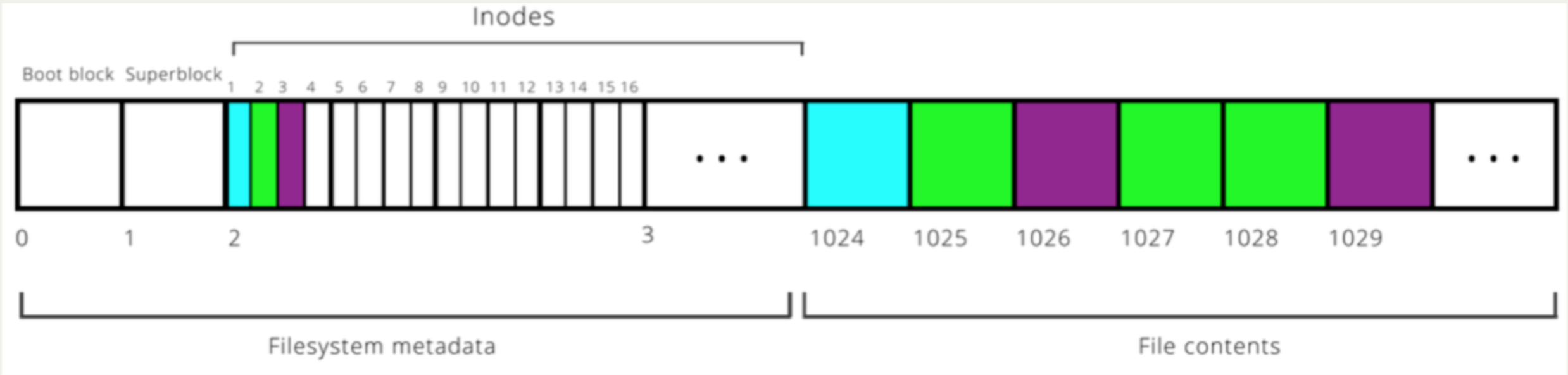

- The filesystem stores inodes on disk together in the inode table for quick access.

- inodes are stored in a reserved region starting at block 2 (block 0 is “boot block” containing hard drive info, block 1 is “superblock” containing filesystem info). Typically at most 10% of the drive stores metadata.

- 16 inodes fit in a single block here.

Filesystem goes from filename to inode number (“inumber”) to file data. (Demo time!)

The inode design here has space for 8 block numbers. The numbers of block is fixed, so a file size has limit. How to build on this to support very large files.

examples:

- remember 1 block = 1 sector = 512 bytes

- file size: 2000 bytes

- block numbers: 56, 122, 45, 22

- Bytes 0-511 reside within block 56, bytes 512-1023 within block 122, bytes 1024-1535 within block 45, and bytes 1536-1999 at the front of block 22.

Indirect Addressing for Large files

Problem: with 8 block numbers per inode, the largest a file can be is 512 * 8 = 4096 bytes (~4KB). That definitely isn’t realistic!

Let’s say a file’s payload is stored across 10 blocks. Assuming that the size of an inode is fixed, where can we put these block numbers?

Solution: let’s store them in a block, and then store that block’s number in the inode! This approach is called indirect addressing.

Each block number is 2 bytes big.

Singly-indirect addressing:

- 8 block numbers in an inode

- 256 block numbers per singly-indirect block

- 512 bytes per block

- the largest a file can be is 8 * 256 * 512 = 1,048,576 bytes (~1MB).

doubly-indirect addressing

- first 7 block numbers in the inode stores block numbers for payload data

- 8th block number in the inode stores singly-indirect block numbers

- 256 + 7 = 263 singly-indirect blocks

- 256 block numbers per singly-indirect block

- 512 bytes per block

- (singly indirect) + (doubly indirect ) = (7 * 256 * 512) + (1 * 256 * 256 * 512) ~ 34MB

File Permissions

- examples: owner(rwx), group(r-x), other(r-x)

- Filesystem represents permissions in binary (1 or 0 for each permission option)

- eg. for permissions above:

111 101 101

- convert each group of 3 from base-2 digit into base-8 digit: 7 5 5

- the permissions for the file would be 755

Directories

A directory is a file container. It needs to store what files/folders are contained within it. It also has associated metadata.

Filesystem model a directory as a file.

- Have an inode for each directory

- A directory’s “payload data” is a list of info about the files it contains

- A directory’s “metadata” is information about it such as its owner

- Inodes can store a field telling us whether something is a directory or file

The Unix V6 filesystem makes directory payloads contain a 16 byte entry for each file/folder that is in that directory.

- The first 14 bytes are the name (not necessarily null-terminated!)

- The last two bytes are the inumber

To find files, we can hop between directory inodes until we reach the inode for our file. We can start at inumber 1 for the root directory.

Hard Links

- It’s possible for two different filenames to resolve to the same inumber.

- Useful if you want multiple copies of a file without having to duplicate its contents.

- If you change the contents of one, the contents of all of them change.

- The inode stores the number of names that resolve to that inode, i_nlink. When that number is 0, and no programs are reading it, the file is deleted.

- What we are describing here is called a hard link. All normal files in Unix (and Linux) are hard links, and two hard links are indistinguishable as far as the file they point to is concerned. In other words, there is no “real” filename, as both file names point to the same inode.

- In Unix, you can create a link using the

ln command.

Soft Links

- A soft link is a special file that contains the path of another file, and has no reference to the inumber.

- The reference count for the original file remains unchanged.

- Again, changing the contents of the file via either filename changes the file.

- If we delete the original file, the soft link breaks! The soft link remains, but the path it refers to is no longer valid. If we had removed the soft link before the file, the original file would still remain.

- To create a soft link in Unix, use the

-s flag with ln.

Design Principles: Modularity & Layering

- sectors -> blocks

- blocks -> files

- files -> inodes

- inodes -> file names

- file names -> path names

- path names -> absolute path names

Filesystem System Calls

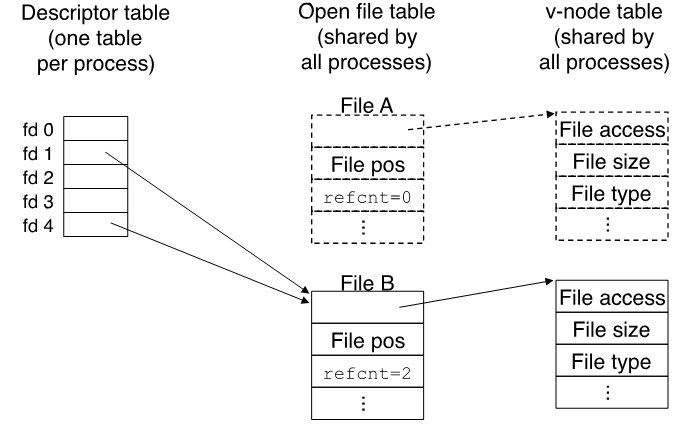

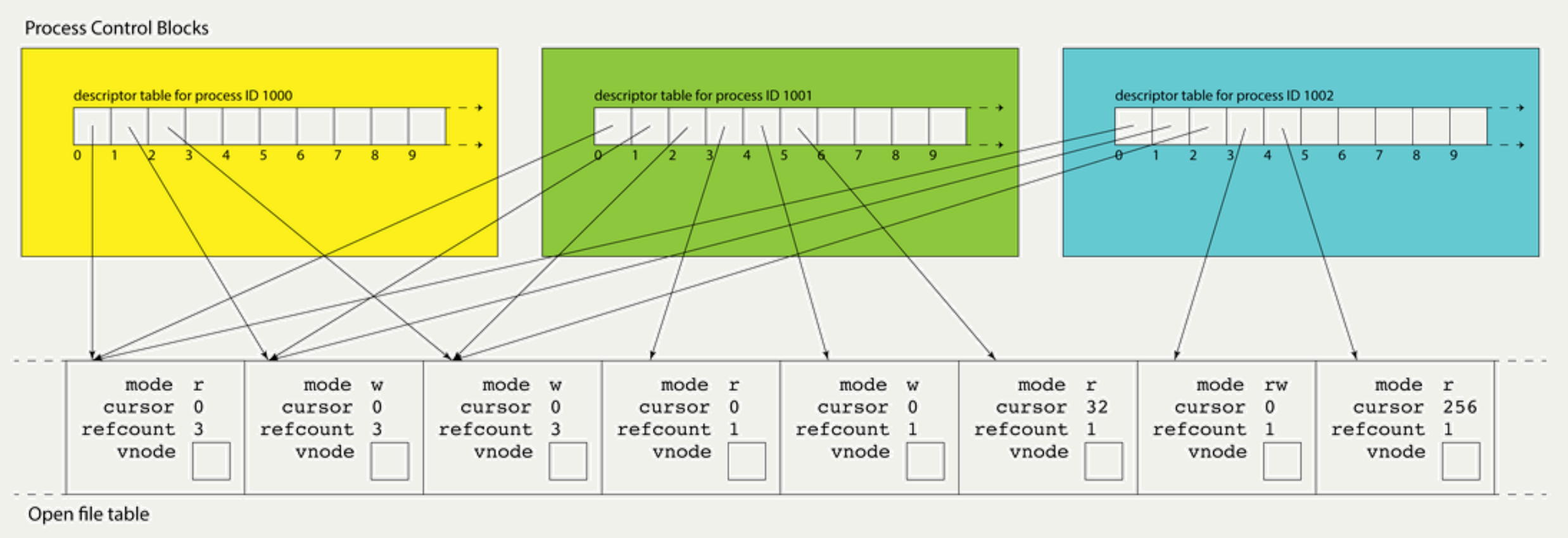

Operating system data structures

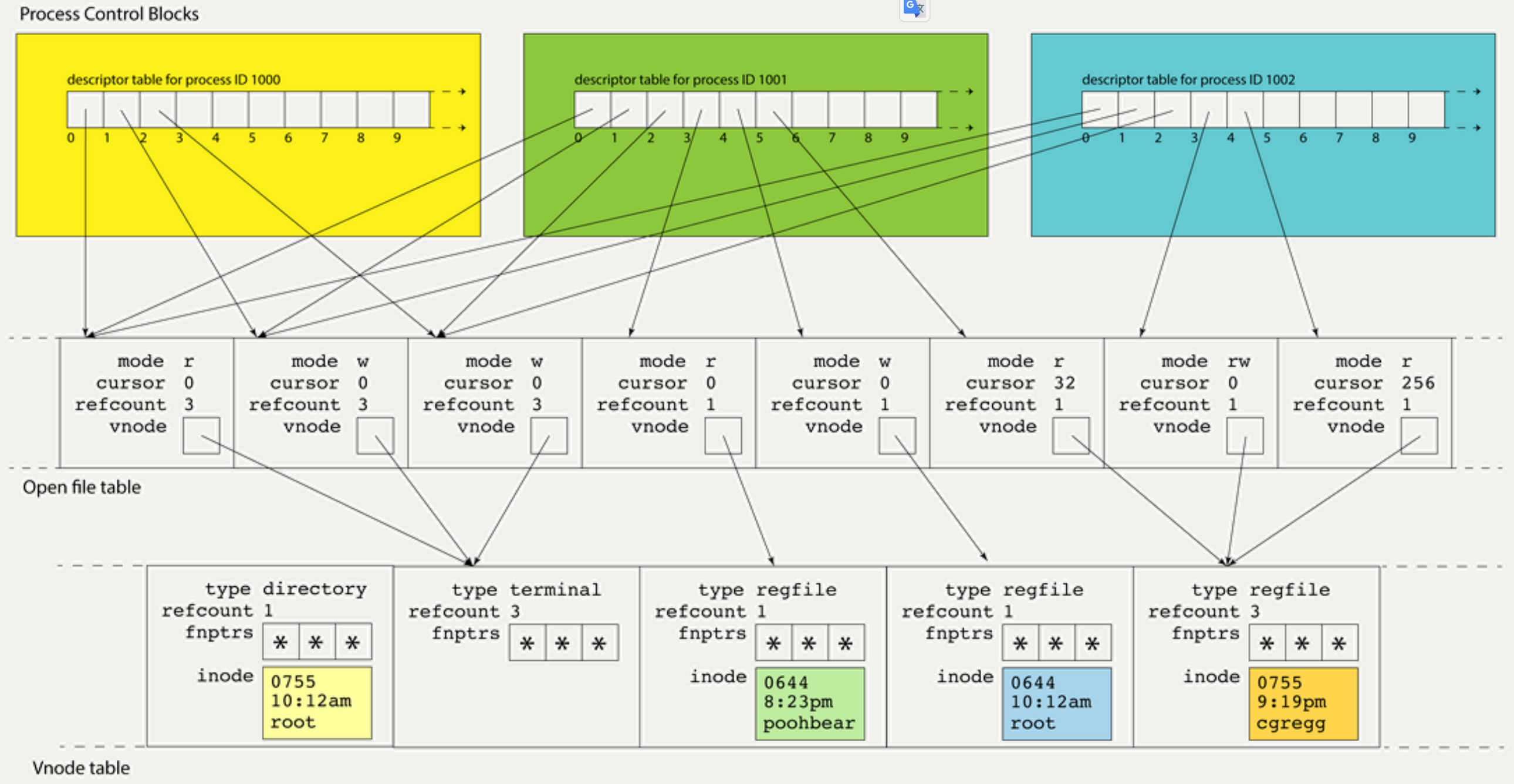

Process Table

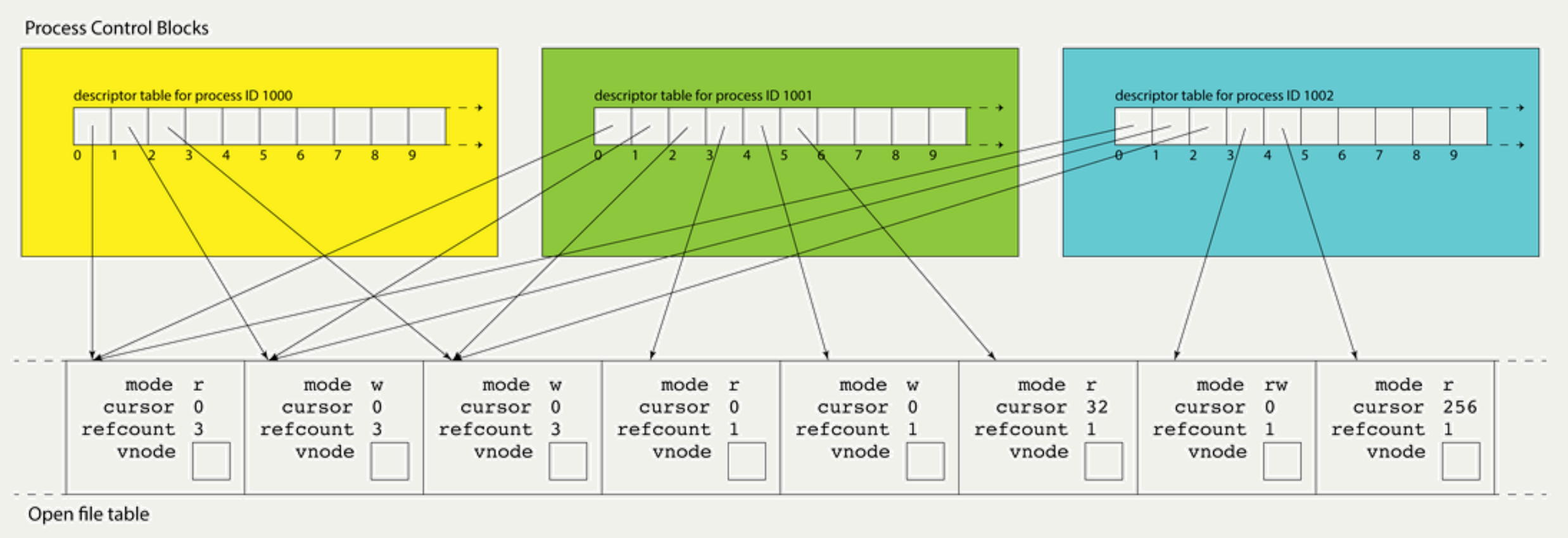

Linux maintains a data structure for each active process. These data structures are called process control blocks, and they are stored in the process table

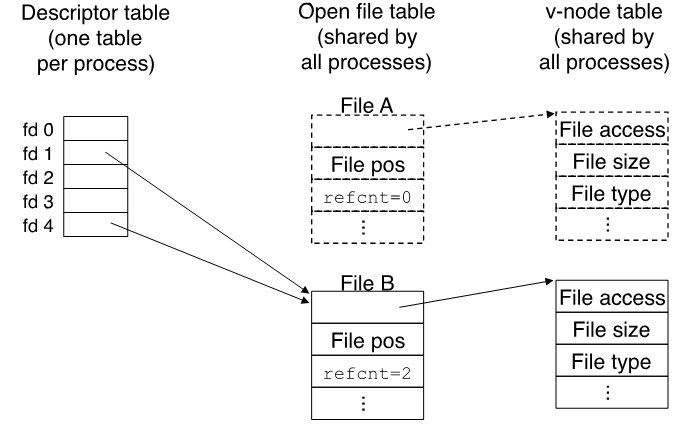

File Descriptor Table

Process control blocks store many things (the user who launched it, what time it was launched, CPU state, etc.). Among the many items it stores is the file descriptor table

A entry in the file descriptor table is just a pointer to a open file table entry.

A file descriptors is a small integer that’s an index into this table - for that reason, we can store and access them just like integers.

There are 3 special file descriptors provided by default to each program:

-

0: standard input (user input from the terminal) - STDIN_FILENO

-

1: standard output (output to the terminal) - STDOUT_FILENO

-

2: standard error (error output to the terminal) - STDERR_FILENO

-

A file descriptor is the identifier needed to interact with a resource (most often a file) via system calls (e.g., read, write, and close)

Open File Table

-

The open file table is one array of information about open files across all processes.

-

Multiple file descriptor entries (even across processes) can point to the same file table entry

-

Entries in different file descriptor tables (different processes!) can point to the same file table entry

-

An open file table entry (for a regular file) keeps track of a current position in the file

- If you read 1000 bytes, the next read will be from 1000 bytes after the preceding one

- If you write 380 bytes, the next write will start 380 bytes after the preceding one

-

If you want multiple processes to write to the same log file and have the results be intelligible, then you have all of them share a single file table entry: their calls to write will be serialized and occur in some linear order

Each process maintains its own descriptor table, but there is one, system-wide open file table. This allows for file resources to be shared between processes.

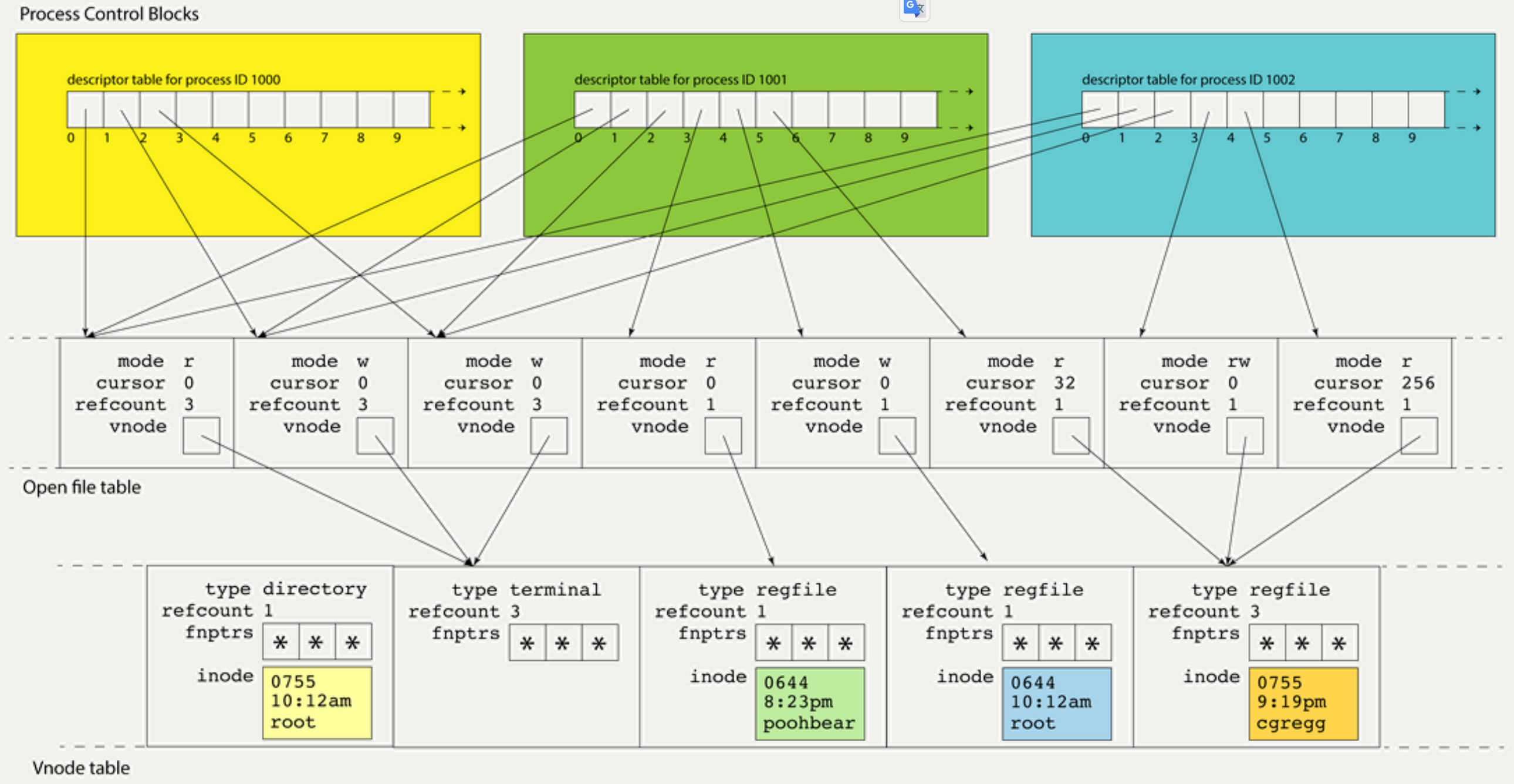

Each open file table entry has a vnode field; a pointer to the file’s static information.

Vnode Table

- Each open file entry has a pointer to a vnode, which is a structure housing static information about a file or file-like resource.

- The vnode is the kernel’s abstraction of an actual file: it includes information on what kind of file it is, how many file table entries reference it, and function pointers for performing operations.

- These resources are all freed over time:

- Free a file table entry when the last file descriptor closes it

- Free a vnode when the last file table entry is freed

- Free a file when its reference count is 0 and there is no vnode

Summary: filesystem layer

There is one system-wide vnode table for the same reason there is one system-wide open file table. Independent file sessions reading from the same file don’t need independent copies of the vnode. They can all alias the same one.

Filesystem inodes of open files are loaded into vnode table entries.

The inode in the vnode is an in-memory replica of the sliver of memory in the filesystem.

Unix IO / System Calls

System calls request services from the OS kernel on the user’s behalf. They are actually “wrappers” of kernel’s routines. For Unix, these wrappers are part of the C standard library, or libc.

Key idea: the OS performs private, privileged tasks that regular user programs cannot do, with data that user programs cannot access.

Regular function calls: data in user-accessible memory, the stack grows downwards to add a new stack frame. Parameters are passed in registers like %rdi and %rsi, and the return value (if any) is put in %rax.

System function calls: a range of addresses will be reserved as “kernel space”; user programs cannot access this memory. Instead of using the user stack and memory space, system calls will use kernel space and execute in a “privileged mode”.

New approach for calling functions if they are system calls:

- put the system call “opcode” in %rax (e.g. 0 for

read, 1 for write, 2 for open, 3 for close, and so forth). Each has its own unique opcode.

- put up to 6 parameters in normal registers except for %rcx (use %r10 instead)

- store the address of the next user program instruction in %rcx instead of %rip

- The syscall assembly instruction triggers a software interrupt that switches execution over to “superuser” mode, transferring the control to the interruption handler function.

- The handler, which resides in the kernel address space, reads the register values to the kernel space and performs the task requested by the system call. The system call executes in privileged mode and puts its return value in %rax, and returns (using iretq, “interrupt” version of retq)

- If %rax is negative, the global errno is set to abs(%rax), and %rax is changed to -1.

- The system transfers control back to the user program.

creat())

1

2

3

4

|

#include <fcntl.h >

int creat(const char *path, mode_t mode);

// Returns: file descriptor opened for write-only if OK, −1 on error

|

The function is equivalent to

1

|

open(path, O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, mode);

|

open()

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

#include <sys/types.h >

#include <sys/stat.h >

#include <fcntl.h >

int open(char *filename, int flags, mode_t mode);

// returns: new file descriptor or -1 on error

|

flags:

- O_RDONLY: read only

- O_WRONLY: write only

- O_RDWR: read and write

- O_TRUNC: if the file exists already, clear (truncate) it

- O_CREAT: create a new file if the specified file doesn’t exist

- O_EXCL: the file must be created from scratch, fail if already exists

mode: the permissions to attempt to set for a created file

1

2

3

4

5

|

// Create the file

int fd = open("myfile.txt", O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_EXCL, 0644);

// Close the file now that we are done with it

close(fd);

|

close()

1

2

3

4

|

#include <unistd.h>

int close(int fd);

// return 0 if ok, -1 on error

|

It’s important to close files when you are done with them to preserve system resources.

You can use valgrind to check if you forgot to close any files.

lseek()

Every open file has an associated ‘‘current file offset,’’ normally a non-negative integer

that measures the number of bytes from the beginning of the file.

Read and write operations normally start at the current file offset and cause the offset to be incremented by the number of bytes read or written. By default, this offset is initialized to 0 when a file is opened, unless the O_APPEND option is specified.

An open file’s offset can be set explicitly by calling lseek.

1

2

3

4

|

#include <unistd.h>

off_t lseek(int fd, off_t offset, int whence);

// return new file offset if OK, -1 on error

|

read()

1

2

3

4

|

#include <unistd.h>

ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);

// Returns: number of bytes read if OK, 0 on EOF, - 1 on error

|

- fd: the file descriptor for the file you’d like to read from

- buf: the memory location where the read-in bytes should be put

- count: the number of bytes you wish to read

- The function returns -1 on error, 0 if at end of file, or nonzero if bytes were read

write()

1

2

3

4

|

#include <unistd.h>

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);

// Returns: number of bytes written if OK, - 1 on error

|

- fd: the file descriptor for the file you’d like to write to

- buf: the memory location storing the bytes that should be written

- count: the number of bytes you wish to write from buf

- The function returns -1 on error, or otherwise the number of bytes that were written

stat()

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

int stat(const char *filename , struct stat *buf);

int fstat(int fd , struct stat *buf);

// Returns: 0 if OK, - 1 on error

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

struct stat st;

lstat(path, &st);

if (S_ISREG(st.st_mode)) {

...

}

else if (S_ISDIR(st.st_mode)) {

...

}

|

dup()

An existing file descriptor is duplicated by either of the following functions.

1

2

3

4

5

|

#include <unistd.h>

int dup(int fd);

int dup2(int oldfd, int newfd);

// Returns: nonnegative descriptor if OK, -1 on error

|

With dup2, we specify the value of the new descriptor with the fd2 argument.

If fd2 is already open, it is first closed.

dup2 implement i/o redirect. for example, dup2(4, 1):

opendir()

1

2

3

|

#include <dirent.h>

DIR *opendir(const char *pathname);

// return: pointer if OK, NULL on error

|

readdir()

1

2

3

4

|

#include <dirent.h>

struct dirent *readdir(DIR *dp);

// Returns: pointer if OK, NULL at end of directory or error

|

closedir()

1

2

3

4

|

#include <dirent.h>

int closedir(DIR *dp);

// Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

|

Implementing touch to emulate touch

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

|

/**

* File: touch.c

* --------------

* This program shows an example of creating a new file with a given

* name. Similar to the `touch` unix command, it creates the file if it

* doesn't exist. But in this case, if it does exist, it throws an error.

*/

#include <fcntl.h> // for open

#include <unistd.h> // for read, write, close

#include <stdio.h>

#include <errno.h>

static const int kDefaultPermissions = 0644; // number equivalent of "rw-r--r--"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// Create the file

int fd = open(argv[1], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_EXCL, kDefaultPermissions);

// If an error occured, print out more information

if (fd == -1) {

printf("There was a problem creating \"%s\"!\n", argv[1]);

if (errno == EEXIST) {

printf("The file already exists.\n");

} else {

printf("Unknown errno: %d\n", errno);

}

return -1;

}

// Close the file now that we are done with it

close(fd);

return 0;

}

|

Implementing copy to emulate cp

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

|

/**

* File: copy.c

* --------------

* This program is the starter code for an example that shows how we can

* make a copy of a specified file into another specified file, similar to the

* `cp` unix command.

*/

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <error.h>

// Constants for different error codes we may return

static const int kWrongArgumentCount = 1;

static const int kSourceFileNonExistent = 2;

static const int kDestinationFileOpenFailure = 4;

static const int kReadFailure = 8;

static const int kWriteFailure = 16;

// The permissions to set if the destination file doesn't exist

static const int kDefaultPermissions = 0644; // number equivalent of "rw-r--r--"

// The number of bytes we copy at once from source to destination

static const int kCopyIncrement = 1024;

/* This function copies the contents of the source file into the destination

* file in chunks until the entire file is copied. If an error occurred

* while reading or writing, this function throws an error.

*/

void copyContents(int sourceFD, int destinationFD) {

char buffer[kCopyIncrement];

while (true) {

// Read the next chunk of bytes from the source

ssize_t bytesRead = read(sourceFD, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

if (bytesRead == 0) break;

if (bytesRead == -1) {

error(kReadFailure, 0, "lost access to file while reading.");

}

// Write that chunk to the destination

size_t bytesWritten = 0;

while (bytesWritten < bytesRead) {

ssize_t count = write(destinationFD, buffer + bytesWritten, bytesRead - bytesWritten);

if (count == -1) {

error(kWriteFailure, 0, "lost access to file while writing.");

}

bytesWritten += count;

}

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// Ensure the user specified 3 arguments

if (argc != 3) {

error(kWrongArgumentCount, 0, "%s <source-file> <destination-file>.", argv[0]);

}

// Open the specified source file for reading

int sourceFD = open(argv[1], O_RDONLY);

if (sourceFD == -1) {

error(kSourceFileNonExistent, 0, "%s: source file could not be opened.", argv[1]);

}

// Open the specified destination file for writing, creating if nonexistent

int destinationFD = open(argv[2], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_EXCL, kDefaultPermissions);

if (destinationFD == -1) {

if (errno == EEXIST) {

error(kDestinationFileOpenFailure, 0, "%s: destination file already exists.", argv[2]);

} else {

error(kDestinationFileOpenFailure, 0, "%s: destination file could not be created.", argv[2]);

}

}

copyContents(sourceFD, destinationFD);

// Close the source file

if (close(sourceFD) == -1) {

error(0, 0, "%s: had trouble closing file.", argv[1]);

}

// Close the destination file

if (close(destinationFD) == -1) {

error(0, 0, "%s: had trouble closing file.", argv[2]);

}

return 0;

}

|

Implementing copy-extended to emulate tee

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

|

/**

* File: copy_extended.c

* --------------

* This program is an implementation of an extended copy command that shows how we can

* make a copy of a specified file into multiple other specified files, as well

* as printing the contents to the terminal.

*/

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <error.h>

// Constants for different error codes we may return

static const int kWrongArgumentCount = 1;

static const int kSourceFileNonExistent = 2;

static const int kDestinationFileOpenFailure = 4;

static const int kReadFailure = 8;

static const int kWriteFailure = 16;

// The permissions to set if the destination file doesn't exist

static const int kDefaultPermissions = 0644; // number equivalent of "rw-r--r--"

// The number of bytes we copy at once from source to destination

static const int kCopyIncrement = 1024;

/* This function copies the contents of the source file into each destination

* file in chunks until the entire file is copied. If an error occurred

* while reading or writing, this function throws an error.

*/

void copyContents(int sourceFD, int destinationFDs[], int numDestinationFDs) {

char buffer[kCopyIncrement];

while (true) {

// Read the next chunk of bytes from the source

ssize_t bytesRead = read(sourceFD, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

if (bytesRead == 0) break;

if (bytesRead == -1) {

error(kReadFailure, 0, "lost access to file while reading.");

}

// Write that chunk to every destination

for (size_t i = 0; i < numDestinationFDs; i++) {

size_t bytesWritten = 0;

while (bytesWritten < bytesRead) {

ssize_t count = write(destinationFDs[i], buffer + bytesWritten, bytesRead - bytesWritten);

if (count == -1) {

error(kWriteFailure, 0, "lost access to file while writing.");

}

bytesWritten += count;

}

}

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// Ensure the user specified 3 arguments

if (argc < 3) {

error(kWrongArgumentCount, 0, "%s <source-file> <destination-file1> <destination-file2> ... .", argv[0]);

}

// Open the specified source file for reading

int sourceFD = open(argv[1], O_RDONLY);

if (sourceFD == -1) {

error(kSourceFileNonExistent, 0, "%s: source file could not be opened.", argv[1]);

}

// Open the specified destination file(s) for writing, creating if nonexistent

int destinationFDs[argc - 1];

// Include the terminal (STDOUT) as the first "file" so it's also printed

destinationFDs[0] = STDOUT_FILENO;

for (size_t i = 2; i < argc; i++) {

destinationFDs[i - 1] = open(argv[i], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_EXCL, kDefaultPermissions);

if (destinationFDs[i - 1] == -1) {

if (errno == EEXIST) {

error(kDestinationFileOpenFailure, 0, "%s: destination file already exists.", argv[2]);

} else {

error(kDestinationFileOpenFailure, 0, "%s: destination file could not be created.", argv[2]);

}

}

}

copyContents(sourceFD, destinationFDs, argc - 1);

// Close the source file

if (close(sourceFD) == -1) {

error(0, 0, "%s: had trouble closing file.", argv[1]);

}

// Close the destination files

for (size_t i = 1; i < argc - 1; i++) {

if (close(destinationFDs[i]) == -1) {

error(0, 0, "%s: had trouble closing file.", argv[2 + i]);

}

}

return 0;

}

|

Using stat and lstat

- stat and lstat

- stat is a function that populates a struct stat with information about some named file (regular files, directories, links).

- stat and lstat operate exactly the same way, except when the named file is a link, stat returns information about the file the link references, and lstat returns information about the link itself.

- The st_mode field isn’t so much a single value as it is a collection of bits encoding multiple pieces of information about file type and permissions.

- A collection of bit masks and macros can be used to extract information from the st_mode field.

Implementing list to emulate ls

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

|

/**

* File: list.c

* ------------

* The program is designed to emulate a very small subset of ls's functionality.

* Specifically, I require that all items to be listed are directories, and I essentially

* implement the executable to be the equivalent of "ls -lUa", save for the fact that I don't

* follow hard links.

*

* This example is presented to be clear that many shell commands like ls, pwd, etc, aren't technically

* shell commands, but standalone executables that just happen to come installed with the OS. It's

* hardly intended to be exhaustive (the real ls has scores of different options).

*/

#include <stdbool.h> // for bool

#include <stddef.h> // for NULL

#include <stdio.h> // for printf

#include <sys/types.h> // for mode_t, uid_t, etc.

#include <sys/stat.h> // for lstat

#include <dirent.h> // for DIR, opendir, etc

#include <string.h> // for strlen, strcpy

#include <pwd.h> // for getpwuid

#include <grp.h> // for getgrgid

#include <time.h> // for time, localtime, etc

#include <unistd.h> // for readlink

static inline void updatePermissionsBit(bool flag, char permissions[], size_t column, char ch) {

if (flag) permissions[column] = ch;

}

static const size_t kNumPermissionColumns = 10;

static const char kPermissionChars[] = {'r', 'w', 'x'};

static const size_t kNumPermissionChars = sizeof(kPermissionChars);

static const mode_t kPermissionFlags[] = {

S_IRUSR, S_IWUSR, S_IXUSR, // user flags

S_IRGRP, S_IWGRP, S_IXGRP, // group flags

S_IROTH, S_IWOTH, S_IXOTH // everyone (other) flags

};

static const size_t kNumPermissionFlags = sizeof(kPermissionFlags)/sizeof(kPermissionFlags[0]);

static void listPermissions(mode_t mode) {

char permissions[kNumPermissionColumns + 1];

memset(permissions, '-', sizeof(permissions));

permissions[kNumPermissionColumns] = '\0';

updatePermissionsBit(S_ISDIR(mode), permissions, 0, 'd');

updatePermissionsBit(S_ISLNK(mode), permissions, 0, 'l');

for (size_t i = 0; i < kNumPermissionFlags; i++) {

updatePermissionsBit(mode & kPermissionFlags[i], permissions, i + 1,

kPermissionChars[i % kNumPermissionChars]);

}

printf("%s ", permissions);

}

static void listHardlinkCount(nlink_t count) {

if (count < 10) printf(" %zu ", count);

else printf(">9 "); // invention of my own so I don't have to worry about column width

}

static void listUser(uid_t uid) {

struct passwd *pw = getpwuid(uid); // first call dynamically allocates memory behind scenes, but can't easily be freed :(

pw == NULL ? printf("%8u ", uid) : printf("%-8s ", pw->pw_name);

}

static void listGroup(gid_t gid) {

struct group *gr = getgrgid(gid); // first call dynamically allocates memory behind scenes, but can't easily be freed :(

const char *group = gr == NULL ? "unknown" : gr->gr_name;

printf("%-8s ", group);

}

static void listSize(off_t size) {

printf("%6zu ", size);

}

static void listModifiedTime(time_t mtime) {

time_t now;

time(&now);

struct tm *currentTime = localtime(&now); // return value not dynamically allocated, invalidated by next call to localtime!

char currentYearString[8];

strftime(currentYearString, sizeof(currentYearString), "%Y", currentTime);

struct tm *modifiedTime = localtime(&mtime);

char modifiedTimeString[32];

strftime(modifiedTimeString, sizeof(modifiedTimeString), "%Y", modifiedTime);

bool sameYear = strcmp(currentYearString, modifiedTimeString) == 0;

const char *format = sameYear ? "%b %d %H:%M" : "%b %d %Y";

strftime(modifiedTimeString, sizeof(modifiedTimeString), format, modifiedTime);

printf("%s ", modifiedTimeString);

}

static void listName(const char *name, const struct stat *st, bool link, const char *path) {

printf("%s", name);

if (!link) return;

char target[st->st_size + 1];

readlink(path, target, sizeof(target));

target[st->st_size] = '\0'; // readlink doesn't put down '\0' char, drop it in ourselves

printf(" -> %s", target);

}

static void listEntry(const char *name, const struct stat *st, bool link, const char *path) {

listPermissions(st->st_mode);

listHardlinkCount(st->st_nlink);

listUser(st->st_uid);

listGroup(st->st_gid);

listSize(st->st_size);

listModifiedTime(st->st_mtime);

listName(name, st, link, path);

printf("\n");

}

static const size_t kMaxPath = 1024;

static void listDirectory(const char *name, size_t length, const struct stat *st, bool multiple) {

char path[kMaxPath + 1];

strcpy(path, name);

if (multiple) printf("%s:\n", name);

DIR *dir = opendir(path);

strcpy(path + length, "/");

while (true) {

struct dirent *de = readdir(dir);

if (de == NULL) break;

strcpy(path + length + 1, de->d_name);

struct stat st;

lstat(path, &st);

listEntry(de->d_name, &st, S_ISLNK(st.st_mode), path);

}

closedir(dir);

}

static void list(const char *name, size_t length, bool multiple) {

if (strlen(name) == 0 || name[0] == '.') return; // ignore what are normally hidden files and directories

struct stat st;

if (lstat(name, &st) == -1) return;

if (S_ISREG(st.st_mode) || S_ISLNK(st.st_mode)) {

listEntry(name, &st, S_ISLNK(st.st_mode), name);

} else if (S_ISDIR(st.st_mode)) {

listDirectory(name, length, &st, multiple);

}

}

static void listEntries(const char *entries[], size_t numEntries) {

bool multiple = numEntries > 1;

for (size_t i = 0; i < numEntries; i++) {

size_t length = strlen(entries[i]);

if (length <= kMaxPath) {

list(entries[i], length, multiple);

} // otherwise ignore

}

}

static const char *kDefaultEntries[] = {".", NULL};

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

const char **entries = argc == 1 ? kDefaultEntries : (const char **)(argv + 1);

size_t numEntries = argc == 1 ? 1 : argc - 1;

listEntries(entries, numEntries);

return 0;

}

|

Implementing search to emulate find

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

|

/**

* File: search.c

* --------------

* Designed to emulate the properties of the GNU find shell program.

* The built-in version of find is much more robust than what we provide here.

*

* To help focus on the file system directives, I omit most error checking from

* this particular implementation.

*/

#include <stdbool.h> // for bool

#include <stddef.h> // for size_t

#include <stdio.h> // for printf, fprintf, etc.

#include <stdlib.h> // for exit

#include <stdarg.h> // for va_list, etc.

#include <sys/stat.h> // for stat

#include <string.h> // for strlen, strcpy, strcmp

#include <dirent.h> // for DIR, struct dirent

static const size_t kMaxPath = 1024;

static const int kWrongArgumentCount = 1;

static const int kDirectoryNeeded = 2;

static void exitUnless(bool test, FILE *stream, int code, const char *control, ...) {

if (test) return;

va_list arglist;

va_start(arglist, control);

vfprintf(stream, control, arglist);

va_end(arglist);

exit(code);

}

static void listMatches(char path[], size_t length, const char *pattern) {

DIR *dir = opendir(path);

if (dir == NULL) return;

strcpy(path + length, "/");

while (true) {

struct dirent *de = readdir(dir);

if (de == NULL) break;

if (strcmp(de->d_name, ".") == 0 || strcmp(de->d_name, "..") == 0) continue;

if (length + strlen(de->d_name) > kMaxPath) continue;

strcpy(path + length + 1, de->d_name);

struct stat st;

lstat(path, &st);

if (S_ISREG(st.st_mode)) {

if (strcmp(de->d_name, pattern) == 0) printf("%s\n", path);

} else if (S_ISDIR(st.st_mode)) {

listMatches(path, length + 1 + strlen(de->d_name), pattern);

}

}

closedir(dir);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

exitUnless(argc == 3, stderr, kWrongArgumentCount, "Usage: %s <directory> <pattern>\n", argv[0]);

const char *directory = argv[1];

struct stat st;

stat(directory, &st);

exitUnless(S_ISDIR(st.st_mode), stderr, kDirectoryNeeded, "<directory> must be an actual directory, %s is not", directory);

size_t length = strlen(directory);

if (length > kMaxPath) return 0;

const char *pattern = argv[2];

char path[kMaxPath + 1];

strcpy(path, directory); // no buffer overflow because of above check

listMatches(path, length, pattern);

return 0;

}

|

Filesystems Recap

- User programs interact with the filesystem via **file descriptors and the **system calls open, close, read and write

- The operating system stores a per-process file descriptor table with pointers to open file table entries containing info about the open files

- The open file table entries point to vnodes, which cache inodes

- inodes are file system representations of files/directories. We can look at an inode to find the blocks containing the file/directory data.

- Inodes can use indirect addressing to support large files/directories

- Key principles: abstraction, layers, naming

Reference