Domain-driven design

The DDD patterns presented in this guide should not be applied universally. They introduce constraints on your design. Those constraints provide benefits such as higher quality over time, especially in commands and other code that modifies system state. However, those constraints add complexity with fewer benefits for reading and querying data.

Steps to Learn Domain-driven Design

- Understand the Principles: Start by familiarizing yourself with the core principles of DDD, such as domain modeling, ubiquitous language, and bounded contexts.

- Read Books and Articles: There are several authoritative books on DDD, including “Domain-Driven Design” by Eric Evans and “Implementing Domain-Driven Design” by Vaughn Vernon. Reading articles and blog posts by DDD practitioners can also provide valuable insights.

- Practical Examples: Look for practical examples and case studies that demonstrate how DDD is applied in real-world scenarios. This can help solidify your understanding of the concepts.

- Online Courses: Consider enrolling in online courses or watching video tutorials dedicated to DDD. Platforms like Coursera, Udemy, and Pluralsight offer courses on this topic.

- Join Communities: Engage with communities and forums where DDD practitioners share their experiences and knowledge. This can provide you with a supportive network and access to valuable resources.

- Apply DDD to Projects: Practice what you learn by applying DDD principles to your own projects or by contributing to open-source projects that utilize DDD.

- Seek Feedback: Share your work with peers or mentors who have experience with DDD. Feedback can help you improve and refine your understanding of DDD concepts.

- Stay Updated: Keep yourself updated with the latest developments and discussions in the DDD community to ensure that you are aware of new techniques and best practices.

Remember that learning DDD is an ongoing process that involves both theoretical understanding and practical application. Good luck on your DDD learning journey!

CQRS and DDD patterns are not top-level architectures

It’s important to understand that CQRS and most DDD patterns (like DDD layers or a domain model with aggregates) are not architectural styles, but only architecture patterns. Microservices, SOA, and event-driven architecture (EDA) are examples of architectural styles. They describe a system of many components, such as many microservices. CQRS and DDD patterns describe something inside a single system or component; in this case, something inside a microservice.

Different Bounded Contexts (BCs) will employ different patterns. They have different responsibilities, and that leads to different solutions. It is worth emphasizing that forcing the same pattern everywhere leads to failure. Do not use CQRS and DDD patterns everywhere. Many subsystems, BCs, or microservices are simpler and can be implemented more easily using simple CRUD services or using another approach.

There is only one application architecture: the architecture of the system or end-to-end application you are designing (for example, the microservices architecture). However, the design of each Bounded Context or microservice within that application reflects its own tradeoffs and internal design decisions at an architecture patterns level. Do not try to apply the same architectural patterns as CQRS or DDD everywhere.

The application layer can be the Web API itself.

ViewModels (data models especially created for the client applications)

Define the boundaries of individual services

Microservices should be designed around business capabilities, not horizontal layers such as data access or messaging. In addition, they should have loose coupling and high functional cohesion. Microservices are loosely coupled if you can change one service without requiring other services to be updated at the same time. A microservice is cohesive if it has a single, well-defined purpose.

DDD has two distinct phases, strategic and tactical. In strategic DDD, you are defining the large-scale structure of the system. Strategic DDD helps to ensure that your architecture remains focused on business capabilities. Tactical DDD provides a set of design patterns that you can use to create the domain model. These patterns include entities, aggregates, and domain services. These tactical patterns will help you to design microservices that are both loosely coupled and cohesive.

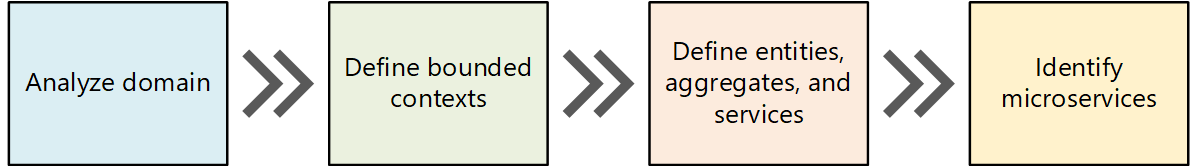

Steps:

- Start by analyzing the business domain to understand the application’s functional requirements. The output of this step is an informal description of the domain, which can be refined into a more formal set of domain models.

- Next, define the bounded contexts of the domain. Each bounded context contains a domain model that represents a particular subdomain of the larger application.

- Within a bounded context, apply tactical DDD patterns to define entities, aggregates, and domain services.

- Use the results from the previous step to identify the microservices in your application.

Analyze the domain

Using a DDD approach will help you to design microservices so that every service forms a natural fit to a functional business requirement.

Before writing any code, you need a bird’s eye view of the system that you are creating. DDD starts by modeling the business domain and creating a domain model. The domain model is an abstract model of the business domain. It distills and organizes domain knowledge, and provides a common language for developers and domain experts.

Define bounded contexts

This is where the DDD concept of bounded contexts comes into play. A bounded context is simply the boundary within a domain where a particular domain model applies. Looking at the previous diagram, we can group functionality according to whether various functions will share a single domain model.

Bounded contexts are not necessarily isolated from one another. In this diagram, the solid lines connecting the bounded contexts represent places where two bounded contexts interact.

Apply tactical DDD

During the strategic phase of domain-driven design (DDD), you are mapping out the business domain and defining bounded contexts for your domain models. Tactical DDD is when you define your domain models with more precision. The tactical patterns are applied within a single bounded context.

In a microservices architecture, we are particularly interested in the entity and aggregate patterns.

Identify microservice boundaries

Defined a set of bounded contexts for an application. Then we looked more closely at one of these bounded contexts, and identified a set of entities, aggregates, and domain services for that bounded context.

Here’s an approach that you can use to derive microservices from the domain model.

- Start with a bounded context. In general, the functionality in a microservice should not span more than one bounded context. By definition, a bounded context marks the boundary of a particular domain model. If you find that a microservice mixes different domain models together, that’s a sign that you may need to go back and refine your domain analysis.

- Next, look at the aggregates in your domain model. Aggregates are often good candidates for microservices.

- Domain services are also good candidates for microservices. Domain services are stateless operations across multiple aggregates.

- Finally, consider non-functional requirements. Look at factors such as team size, data types, technologies, scalability requirements, availability requirements, and security requirements. These factors may lead you to further decompose a microservice into two or more smaller services, or do the opposite and combine several microservices into one.

Layered Architecture

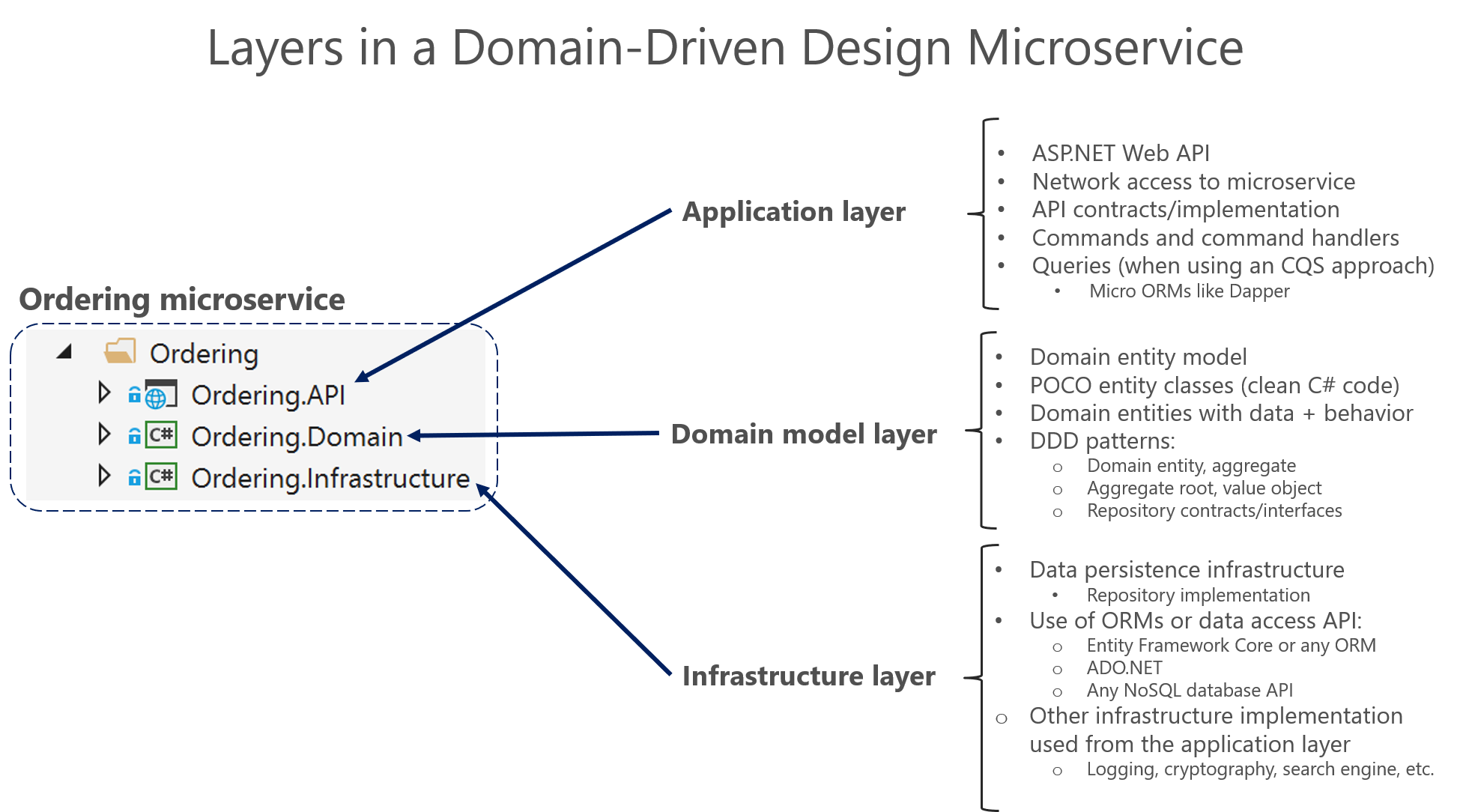

The point here is that the domain entity is contained within the domain model layer and should not be propagated to other areas that it does not belong to, like to the presentation layer.

Additionally, you need to have always-valid entities controlled by aggregate roots (root entities). Therefore, entities should not be bound to client views, because at the UI level some data might still not be validated. This reason is what the ViewModel is for. The ViewModel is a data model exclusively for presentation layer needs. The domain entities do not belong directly to the ViewModel. Instead, you need to translate between ViewModels and domain entities and vice versa.

When tackling complexity, it is important to have a domain model controlled by aggregate roots that make sure that all the invariants and rules related to that group of entities (aggregate) are performed through a single entry-point or gate, the aggregate root.

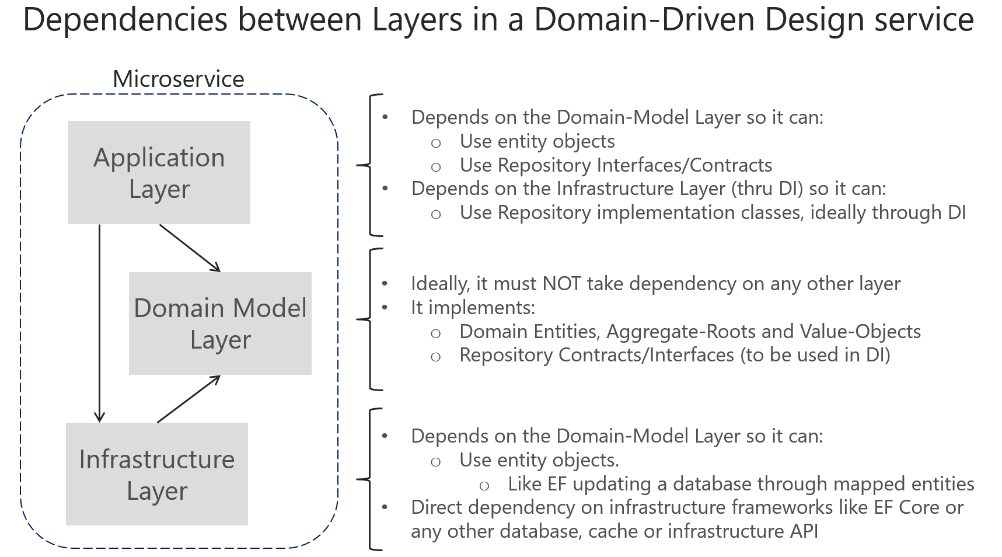

Dependencies in a DDD Service, the Application layer depends on Domain and Infrastructure, and Infrastructure depends on Domain, but Domain doesn’t depend on any layer. This layer design should be independent for each microservice. As noted earlier, you can implement the most complex microservices following DDD patterns, while implementing simpler data-driven microservices (simple CRUD in a single layer) in a simpler way.

Presentation layer

Application layer

This layer is kept thin. It does not contain business rules or knowledge, but only coordinates tasks and delegates work to collaborations of domain objects in the next layer down.

A microservice’s application layer is commonly coded as a Web API project.

It includes queries if using a CQRS approach, commands accepted by the microservice, and even the event-driven communication between microservices (integration events).

The Web API that represents the application layer must not contain business rules or domain knowledge (especially domain rules for transactions or updates); these should be owned by the domain model layer. The application layer must only coordinate tasks and must not hold or define any domain state (domain model). It delegates the execution of business rules to the domain model classes themselves (aggregate roots and domain entities), which will ultimately update the data within those domain entities.

Basically, the application logic is where you implement all use cases that depend on a given front end. For example, the implementation related to a Web API service.

Domain model layer

This layer is the heart of business software.

The domain model layer is where the business is expressed.

Following the Persistence Ignorance and the Infrastructure Ignorance principles, this layer must completely ignore data persistence details. These persistence tasks should be performed by the infrastructure layer. Therefore, this layer should not take direct dependencies on the infrastructure, which means that an important rule is that your domain model entity classes should be POCOs.

Most modern ORM frameworks allow this approach, so that your domain model classes are not coupled to the infrastructure.

Infrastructure layer

You must keep the domain model entity classes agnostic from the infrastructure that you use to persist data (EF or any other framework) by not taking hard dependencies on frameworks.

Persistence is infrastructure.

Common patterns

The Modules pattern

It is a truism that there should be low coupling between MODULES and high cohesion within them.

The code within a module should be highly cohesive and there should be low coupling between classes of different modules.

At the same time, the elements of a good model have synergy, and well-chosen MODULES bring together elements of the model with particularly rich conceptual relationships. This high cohesion of objects with related responsibilities allows modeling and design work to concentrate within a single MODULE, a scale of complexity a human mind can easily handle.

The name of the MODULE conveys its meaning.

The Services pattern

When part of a program’s functionality does not conceptually belong to any object, it is typically expressed as a service.

In some cases, the clearest and most pragmatic design includes operations that do not conceptually belong to any object. Rather than force the issue, we can follow the natural contours of the problem space and include SERVICES explicitly in the model.

A SERVICE is an operation offered as an interface that stands alone in the model, without encapsulating state, as ENTITIES and VALUE OBJECTS do. SERVICES are a common pattern in technical frameworks, but they can also apply in the domain layer.

This pattern is focused on those SERVICES that have an important meaning in the domain in their own right, but of course SERVICES are not used only in the domain layer. It takes care to distinguish SERVICES that belong to the domain layer from those of other layers, and to factor responsibilities to keep that distinction sharp.

Partitioning Services into Layers: Application layer, Domain layer, Infrastructure layer.

The Factories pattern

In domain-driven design, an object’s creation is often separated from the object itself.

A factory is an object with methods for directly creating domain objects.

Design the application layer and Web API

Use SOLID principles and Dependency Injection

SOLID is an acronym that groups five fundamental principles:

- Single Responsibility principle

- Open/closed principle

- Liskov substitution principle

- Interface Segregation principle

- Dependency Inversion principle

SOLID is more about how you design your application or microservice internal layers and about decoupling dependencies between them. It is not related to the domain, but to the application’s technical design. The final principle, the Dependency Inversion principle, allows you to decouple the infrastructure layer from the rest of the layers, which allows a better decoupled implementation of the DDD layers.

Dependency Injection (DI) is one way to implement the Dependency Inversion principle. It is a technique for achieving loose coupling between objects and their dependencies. Rather than directly instantiating collaborators, or using static references (that is, using new…), the objects that a class needs in order to perform its actions are provided to (or “injected into”) the class. Most often, classes will declare their dependencies via their constructor, allowing them to follow the Explicit Dependencies principle. Dependency Injection is usually based on specific Inversion of Control (IoC) containers.

By following the SOLID principles, your classes will tend naturally to be small, well-factored, and easily tested.

Design the domain model layer

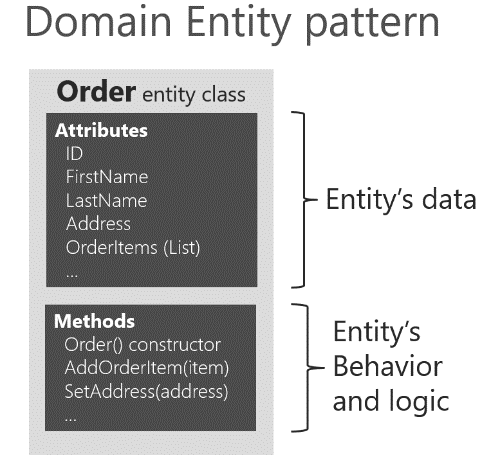

The Domain Entity pattern

Entities represent domain objects. Entities are very important in the domain model, since they are the base for a model. The context of each microservice or Bounded Context impacts its domain model.

Domain entities must implement behavior in addition to implementing data attributes.

A domain entity in DDD must implement the domain logic or behavior related to the entity data (the object accessed in memory). For example, as part of an order entity class you must have business logic and operations implemented as methods for tasks such as adding an order item, data validation, and total calculation. The entity’s methods take care of the invariants and rules of the entity instead of having those rules spread across the application layer.

A domain model entity implements behaviors through methods, that is, it’s not an “anemic” model. Of course, sometimes you can have entities that do not implement any logic as part of the entity class. This can happen in child entities within an aggregate if the child entity does not have any special logic because most of the logic is defined in the aggregate root. If you have a complex microservice that has logic implemented in the service classes instead of in the domain entities, you could be falling into the anemic domain model.

Rich domain model versus anemic domain model

The catch comes when you look at the behavior, and you realize that there is hardly any behavior on these objects, making them little more than bags of getters and setters.

The anemic domain model is just a procedural style design. Anemic entity objects are not real objects because they lack behavior (methods). They only hold data properties and thus it is not object-oriented design. By putting all the behavior out into service objects (the business layer), you essentially end up with spaghetti code or transaction scripts, and therefore you lose the advantages that a domain model provides.

Regardless, if your microservice or Bounded Context is very simple (a CRUD service), the anemic domain model in the form of entity objects with just data properties might be good enough, and it might not be worth implementing more complex DDD patterns. In that case, it will be simply a persistence model, because you have intentionally created an entity with only data for CRUD purposes.

Some people say that the anemic domain model is an anti-pattern. It really depends on what you are implementing. If the microservice you are creating is simple enough (for example, a CRUD service), following the anemic domain model it is not an anti-pattern. However, if you need to tackle the complexity of a microservice’s domain that has a lot of ever-changing business rules, the anemic domain model might be an anti-pattern for that microservice or Bounded Context. In that case, designing it as a rich model with entities containing data plus behavior as well as implementing additional DDD patterns (aggregates, value objects, etc.) might have huge benefits for the long-term success of such a microservice.

The Value Object pattern

An entity requires an identity, but there are many objects in a system that do not, like the Value Object pattern. Examples include numbers and strings, but can also be higher-level concepts like groups of attributes.

For example, an address in an e-commerce application might not have an identity at all, since it might only represent a group of attributes of the customer’s profile for a person or company. In this case, the address should be classified as a value object. However, in an application for an electric power utility company, the customer address could be important for the business domain. Therefore, the address must have an identity so the billing system can be directly linked to the address. In that case, an address should be classified as a domain entity.

The Aggregate pattern

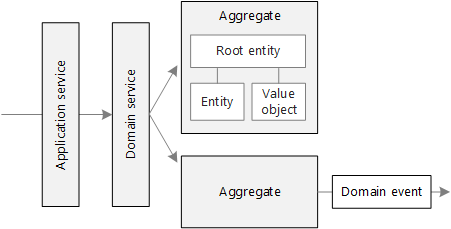

A domain model contains clusters of different data entities and processes that can control a significant area of functionality, such as order fulfillment or inventory. A more fine-grained DDD unit is the aggregate, which describes a cluster or group of entities and behaviors that can be treated as a cohesive unit.

You usually define an aggregate based on the transactions that you need. A classic example is an order that also contains a list of order items. An order item will usually be an entity. But it will be a child entity within the order aggregate, which will also contain the order entity as its root entity, typically called an aggregate root.

Identifying aggregates can be hard. An aggregate is a group of objects that must be consistent together, but you cannot just pick a group of objects and label them an aggregate. You must start with a domain concept and think about the entities that are used in the most common transactions related to that concept. Those entities that need to be transactionally consistent are what forms an aggregate. Thinking about transaction operations is probably the best way to identify aggregates.

The Aggregate Root or Root Entity pattern

An aggregate is composed of at least one entity: the aggregate root, also called root entity or primary entity. Additionally, it can have multiple child entities and value objects, with all entities and objects working together to implement required behavior and transactions.

The purpose of an aggregate root is to ensure the consistency of the aggregate; it should be the only entry point for updates to the aggregate through methods or operations in the aggregate root class. You should make changes to entities within the aggregate only via the aggregate root. It is the aggregate’s consistency guardian, considering all the invariants and consistency rules you might need to comply with in your aggregate. If you change a child entity or value object independently, the aggregate root cannot ensure that the aggregate is in a valid state. It would be like a table with a loose leg. Maintaining consistency is the main purpose of the aggregate root.

A DDD domain model is composed from aggregates, an aggregate can have just one entity or more, and can include value objects as well.

The Domain Events pattern

Domain events can be used to notify other parts of the system when something happens. Domain events are especially relevant in a microservices architecture. Because microservices are distributed and don’t share data stores, domain events provide a way for microservices to coordinate with each other.

Domain events include asynchronous messaging in interservice communication.

Design the infrastructure layer

Design the infrastructure persistence layer

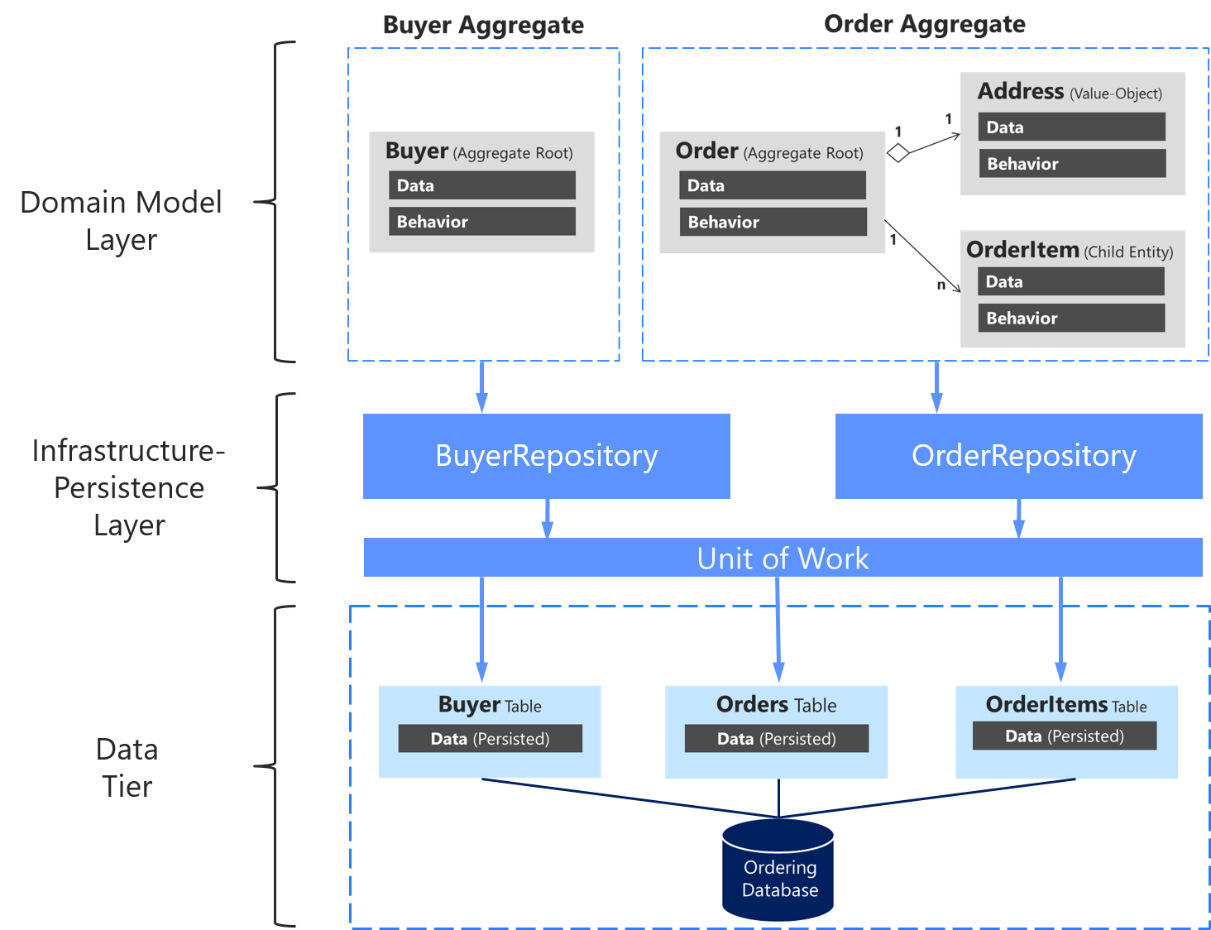

Data persistence components provide access to the data hosted within the boundaries of a microservice (that is, a microservice’s database). They contain the actual implementation of components such as repositories and Unit of Work classes, like custom Entity Framework (EF) DbContext objects. EF DbContext implements both the Repository and the Unit of Work patterns.

The Repository pattern

For each aggregate or aggregate root, you should create one repository class.

Repositories save and dispense aggregate roots.

In domain-driven design, an object’s creation is often separated from the object itself.

A repository, for instance, is an object with methods for retrieving domain objects from a data store (e.g. a database).

Where do you go to retrieve entities? How do you store them? These questions are answered by the Repository pattern. Repositories represent an in-memory collection, and the conventional wisdom is that you end up with one repository per aggregate root.

This separation of model code from infrastructure is a good attribute.

In a microservice based on Domain-Driven Design (DDD) patterns, the only channel you should use to update the database should be the repositories. This is because they have a one-to-one relationship with the aggregate root, which controls the aggregate’s invariants and transactional consistency. It’s okay to query the database through other channels (as you can do following a CQRS approach), because queries don’t change the state of the database. However, the transactional area (that is, the updates) must always be controlled by the repositories and the aggregate roots.

Basically, a repository allows you to populate data in memory that comes from the database in the form of the domain entities. Once the entities are in memory, they can be changed and then persisted back to the database through transactions.

It’s important to emphasize again that you should only define one repository for each aggregate root. To achieve the goal of the aggregate root to maintain transactional consistency between all the objects within the aggregate, you should never create a repository for each table in the database.

Repositories might be useful, but they are not critical for your DDD design in the way that the Aggregate pattern and a rich domain model are. Therefore, use the Repository pattern or not, as you see fit.

The difference between the Repository pattern and the legacy Data Access class (DAL class) pattern:

- A typical DAL object directly performs data access and persistence operations against storage, often at the level of a single table and row. Most DAL class approaches make minimal use of abstractions, resulting in tight coupling between application or Business Logic Layer (BLL) classes that call the DAL objects.

- When using repository, the implementation details of persistence are encapsulated away from the domain model.

Unit of Work

A unit of work refers to a single transaction that involves multiple insert, update, or delete operations. In simple terms, it means that for a specific user action, such as a registration on a website, all the insert, update, and delete operations are handled in a single transaction.

The selected ORM can optimize the execution against the database by grouping several update actions within the same transaction.

The Unit of Work pattern can be implemented with or without using the Repository pattern.

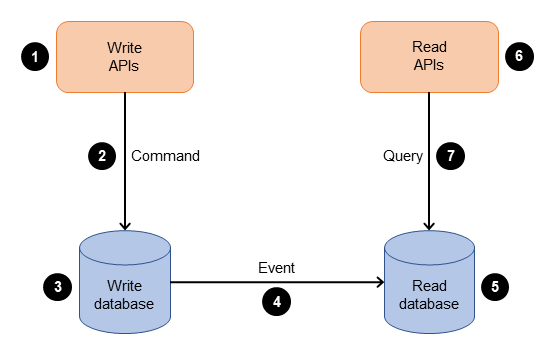

CQRS pattern

CQRS separates reads and writes into different models, using commands to update data, and queries to read data.

- Commands should be task-based, rather than data centric.

- Commands may be placed on a queue for asynchronous processing, rather than being processed synchronously.

- Queries never modify the database. A query returns a DTO that does not encapsulate any domain knowledge.

The models can then be isolated although that’s not an absolute requirement. For greater isolation, you can physically separate the read data from the write data. In that case, the read database can use its own data schema that is optimized for queries. For example, it can store a materialized view of the data, in order to avoid complex joins or complex O/RM mappings. It might even use a different type of data store. For example, the write database might be relational, while the read database is a document database. If separate read and write databases are used, they must be kept in sync. Typically this is accomplished by having the write model publish an event whenever it updates the database.

The read store can be a read-only replica of the write store, or the read and write stores can have a different structure altogether. Using multiple read-only replicas can increase query performance, especially in distributed scenarios where read-only replicas are located close to the application instances.

Some implementations of CQRS use the Event Sourcing pattern. With this pattern, application state is stored as a sequence of events.

The command query responsibility segregation (CQRS) pattern separates the data mutation, or the command part of a system, from the query part. You can use the CQRS pattern to separate updates and queries if they have different requirements for throughput, latency, or consistency. The CQRS pattern splits the application into two parts—the command side and the query side. The command side handles create, update, and delete requests. The query side runs the query part by using the read replicas.

The application processes the incoming command on the command side. This involves validating, authorizing, and running the operation.

After the command is stored in the write database, events are triggered to update the data in the read (query) database.

You can implement the CQRS pattern by using various combinations of databases, including:

- Using relational database management system (RDBMS) databases for both the command and the query side. Write operations go to the primary database and read operations can be routed to read replicas.

- Using an RDBMS database for the command side and a NoSQL database for the query side.

- Using NoSQL databases for both the command and the query side.

- Using a NoSQL database for the command side and an RDBMS database for the query side.

A NoSQL data store is used to optimize the write throughput and provide flexible query capabilities.

A relational database provides complex query functionality.

You should consider using the CQRS pattern if:

- You implemented the database-per-service pattern and want to join data from multiple microservices.

- Your read and write workloads have separate requirements for scaling, latency, and consistency.

- Eventual consistency is acceptable for the read queries.

Benefits of CQRS include:

- Independent scaling. CQRS allows the read and write workloads to scale independently, and may result in fewer lock contentions.

- Optimized data schemas. The read side can use a schema that is optimized for queries, while the write side uses a schema that is optimized for updates.

- Security. It’s easier to ensure that only the right domain entities are performing writes on the data.

- Separation of concerns. Segregating the read and write sides can result in models that are more maintainable and flexible. Most of the complex business logic goes into the write model. The read model can be relatively simple.

- Simpler queries. By storing a materialized view in the read database, the application can avoid complex joins when querying.

Some challenges of implementing this pattern include:

- Complexity. The basic idea of CQRS is simple. But it can lead to a more complex application design, especially if they include the Event Sourcing pattern.

- Messaging. Although CQRS does not require messaging, it’s common to use messaging to process commands and publish update events. In that case, the application must handle message failures or duplicate messages.

- Eventual consistency. If you separate the read and write databases, the read data may be stale. The read model store must be updated to reflect changes to the write model store, and it can be difficult to detect when a user has issued a request based on stale read data.

Event Sourcing pattern

Reference

Using domain analysis to model microservices

Using tactical DDD to design microservices

Design a microservice domain model