What are Microservices?

Architecture

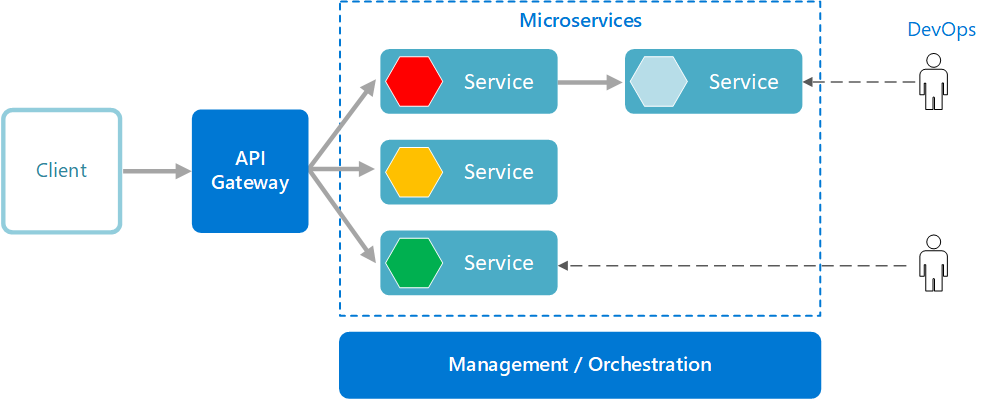

A microservices architecture consists of a collection of small, autonomous services. Each service is self-contained and should implement a single business capability within a bounded context. A bounded context is a natural division within a business and provides an explicit boundary within which a domain model exists.

Characteristics

- Microservices are small, independent, and loosely coupled.

- Each service is a separate codebase.

- Services can be deployed independently.

- Services are responsible for persisting their own data or external state. This differs from the traditional model, where a separate data layer handles data persistence.

- Services communicate with each other by using well-defined APIs. Internal implementation details of each service are hidden from other services.

- Supports polyglot programming. For example, services don’t need to share the same technology stack, libraries, or frameworks.

Components

-

Management/orchestration

This component is responsible for placing services on nodes, identifying failures, rebalancing services across nodes, and so forth. Typically this component is an off-the-shelf technology such as Kubernetes, rather than something custom built.

-

API Gateway

The API gateway is the entry point for clients. Instead of calling services directly, clients call the API gateway, which forwards the call to the appropriate services on the back end.

Advantages of using an API gateway include:

- It decouples clients from services. Services can be versioned or refactored without needing to update all of the clients.

- Services can use messaging protocols that are not web friendly, such as AMQP.

- The API Gateway can perform other cross-cutting functions such as authentication, logging, SSL termination, and load balancing.

- Out-of-the-box policies, like for throttling, caching, transformation, or validation.

Benefits

- Agility. Because microservices are deployed independently, it’s easier to manage bug fixes and feature releases.

- Small, focused teams. Small team sizes promote greater agility.

- Small code base. In a monolithic application, there is a tendency over time for code dependencies to become tangled. Adding a new feature requires touching code in a lot of places. By not sharing code or data stores, a microservices architecture minimizes dependencies, and that makes it easier to add new features.

- Mix of technologies. Teams can pick the technology that best fits their service, using a mix of technology stacks as appropriate.

- Fault isolation. If an individual microservice becomes unavailable, it won’t disrupt the entire application, as long as any upstream microservices are designed to handle faults correctly. For example, you can implement the Circuit Breaker pattern, or you can design your solution so that the microservices communicate with each other using asynchronous messaging patterns.

- Scalability. Services can be scaled independently, letting you scale out subsystems that require more resources, without scaling out the entire application. Using an orchestrator such as Kubernetes or Service Fabric, you can pack a higher density of services onto a single host, which allows for more efficient utilization of resources.

- Data isolation. It is much easier to perform schema updates, because only a single microservice is affected. In a monolithic application, schema updates can become very challenging, because different parts of the application might all touch the same data, making any alterations to the schema risky.

Challenges

- Complexity. Each service is simpler, but the entire system as a whole is more complex.

- Development and testing. Writing a small service that relies on other dependent services requires a different approach than a writing a traditional monolithic or layered application. It is also challenging to test service dependencies.

- Lack of governance. You might end up with so many different languages and frameworks that the application becomes hard to maintain. It might be useful to put some project-wide standards in place, without overly restricting teams’ flexibility.

- Network congestion and latency. The use of many small, granular services can result in more inter-service communication. Also, if the chain of service dependencies gets too long (service A calls B, which calls C…), the additional latency can become a problem. You will need to design APIs carefully. Avoid overly chatty APIs, think about serialization formats, and look for places to use asynchronous communication patterns like queue-based load leveling.

- Data integrity. With each microservice responsible for its own data persistence. As a result, data consistency can be a challenge. Embrace eventual consistency where possible.

- Management. To be successful with microservices requires a mature DevOps culture. Correlated logging across services can be challenging. Typically, logging must correlate multiple service calls for a single user operation.

- Versioning. Updates to a service must not break services that depend on it. Multiple services could be updated at any given time, so without careful design, you might have problems with backward or forward compatibility.

- Skill set. Microservices are highly distributed systems. Carefully evaluate whether the team has the skills and experience to be successful.

Best practices

- Model services around the business domain.

- Decentralize everything. Individual teams are responsible for designing and building services. Avoid sharing code or data schemas.

- Data storage should be private to the service that owns the data. Use the best storage for each service and data type.

- Services communicate through well-designed APIs. Avoid leaking implementation details. APIs should model the domain, not the internal implementation of the service.

- Avoid coupling between services. Causes of coupling include shared database schemas and rigid communication protocols.

- Offload cross-cutting concerns, such as authentication and SSL termination, to the gateway.

- Keep domain knowledge out of the gateway. The gateway should handle and route client requests without any knowledge of the business rules or domain logic. Otherwise, the gateway becomes a dependency and can cause coupling between services.

- Services should have loose coupling and high functional cohesion. Functions that are likely to change together should be packaged and deployed together. If they reside in separate services, those services end up being tightly coupled, because a change in one service will require updating the other service. Overly chatty communication between two services may be a symptom of tight coupling and low cohesion.

- Isolate failures. Use resiliency strategies to prevent failures within a service from cascading. See Resiliency patterns and Designing reliable applications.

Design Patterns

Gateway Routing

Gateway Aggregation

Gateway Offloading

Offload some features into a gateway, particularly cross-cutting concerns such as certificate management, authentication, SSL termination, monitoring, protocol translation, or throttling.

Circuit Breaker

Rate Limiting

Microservices with Python

Gateway Interface

When your code uses this standard, your project can be executed by standard web servers like Apache or nginx, using WSGI extensions like uwsgi or mod_wsgi.

WSGI (Web Server Gateway Interface)

WSGI provided a standard for synchronous Python application.

Gunicorn

uWSGI

Django

Tornado

Pyramid

ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface)

ASGI provides one for both asynchronous and synchronous applications, with a WSGI backwards-compatibility implementation and multiple servers and application frameworks.

Asynchronous applications

A worker pool approach

When an application has lots of requests arriving, an effective strategy is to ensure that all the heavy lifting is done using other processes or threads. Starting a new thread can be slow, and starting a new process is even slower, and so a common technique is to start these workers early and keep them around, giving them new work to do as it arrives.

Twisted, Tornado, Greenlets, and Gevent

For a long time, non-WSGI frameworks like Twisted and Tornado were the popular answers for concurrency when using Python, allowing developers to specify callbacks for many simultaneous requests. A callback is a technique where the calling part of the program doesn’t wait but instead tells the function what it should do with the result it generates. Often this is another function that it should call.

Another popular approach involved Greenlets and Gevent.

Greenlets are pseudo-threads that are very cheap to instantiate, unlike real threads, and that can be used to call Python functions. Within those functions, you can switch, and give back the control to another function. The switching is done with an event loop and allows you to write an asynchronous application using a thread-like interface paradigm. However, switching from one greenlet to another has to be done explicitly, and the resulting code can quickly become messy and hard to understand. That’s where Gevent can become very useful.

The Gevent project is built on top of Greenlet and offers an implicit and automatic way of switching between greenlets, among many other things.

Asynchronous Python

The way the Python core developers coded asyncio, and how they extended the language with the async and await keywords to implement coroutines, made asynchronous applications built with vanilla Python 3.5+ code look very elegant and close to synchronous programming.

aiohttp is one of the most mature asyncio packages.

aiopg is a PostgreSQL library for asyncio.

If you need to use a library that is not asynchronous in your code, to use it from your asynchronous code means that you will need to go through some extra and challenging work if you want the different libraries to work well together.

Synchronous Applications

Synchronous frameworks

There are many great synchronous frameworks to build microservices with Python, like Bottle, Pyramid with Cornice, or Flask.

Language performance

The two different ways to write microservices: asynchronous versus synchronous, and whatever technique you use, the speed of Python directly impacts the performance of your microservice.

Python is slower than Java or Go, but execution speed is not always the top priority. Its core speed is usually less important than how fast your SQL queries will take to return from your Postgres server, because the latter will represent most of the time spent building the response.

It’s also important to remember that how long you spend developing the software can be just as important. If your services are rapidly changing, or a new developer joins and has to understand the code, it is important to have code that is easy to understand, develop, and deploy.

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) can affect performance, because multithreaded applications cannot use several processes. For microservices, besides preventing the usage of multiple cores in the same process, the GIL will slightly degrade performance under high load because of the system calls overhead introduced by the mutex.

Bear in mind that even if the core team removes all the GIL performance issues, Python is an interpreted and garbage collected language and suffers performance penalties for those properties.

There are ways to speed up Python execution:

-

One is to write a part of your code in compiled code by building extensions in C, Rust, or another compiled language, or using a static extension of the language like Cython, but that makes your code more complicated.

-

Another solution is by simply running your application using the PyPy interpreter. This can give noticeable performance improvements just by swapping out the Python interpreter.

PyPy implements a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler. This compiler directly replaces, at runtime, pieces of Python with machine code that can be directly used by the CPU. The whole trick for the JIT compiler is to detect in real time, ahead of the execution, when and how to do it.

Testing

Unit tests

Python’s standard library comes with everything needed to write unit tests.

Functional tests

Functional tests for a microservice project are all the tests that interact with the published API by sending HTTP requests, and asserting that the HTTP responses are the expected ones.

Using pytest to automatically discover and run all the tests in a project.

The useful extensions of pytest are pytest-black, pytest-cov and pytest-flake8.

The first one uses the coverage tool to display the test coverage of your project, and the second one runs the Flake8 linter to make sure that your code is following the PEP8 style, and avoids a variety of other problems.

Another useful tool that can be used in conjunction with pytest is tox. If your projects need to run on several versions of Python or in several different environments, tox can automate the creation of these separate environments to run your tests.

Integration tests

Unit tests and functional tests focus on testing your service code without calling other network resources, and so no other microservices in your application, or third-party services such as databases, need to be available. For the sake of speed, isolation, and simplicity, network calls are mocked.

Integration tests are functional tests without any mocking and should be able to run on a real deployment of your application. For example, if your service interacts with Redis and RabbitMQ, they will be called by your service as normal when the integration tests are run.

Load tests

The information from load tests will, alongside numbers collected from the production service, allow you to balance your service’s throughput with the number of queries it can reasonably respond to simultaneously, the amount of work that needs doing for a response, how long queries wait for a response, and how much the service will cost—this is known as capacity management.

Depending on the kind of load you want to achieve, there are many tools available, from simple command-line tools to heavier distributed load systems.

Salvo is an Apache Bench (AB) equivalent written in Python.

Molotov is a simple to write load tests.

End-to-end tests

An end-to-end test will check that the whole system works as expected from the end-user point of view. Using a tool like Selenium to write end-to-end tests.

Messaging

Asynchronous messaging and event-driven communication are critical when propagating changes across multiple microservices and their related domain models. As mentioned earlier in the discussion microservices and Bounded Contexts (BCs), models (User, Customer, Product, Account, etc.) can mean different things to different microservices or BCs. That means that when changes occur, you need some way to reconcile changes across the different models. A solution is eventual consistency and event-driven communication based on asynchronous messaging.

A message is composed by a header (metadata such as identification or security information) and a body. Messages are usually sent through asynchronous protocols like AMQP.

Another rule you should try to follow, as much as possible, is to use only asynchronous messaging between the internal services, and to use synchronous communication (such as HTTP) only from the client apps to the front-end services (API Gateways plus the first level of microservices).

Message Queueing

Message-based asynchronous communication with a single receiver means there’s point-to-point communication that delivers a message to exactly one of the consumers that’s reading from the channel, and that the message is processed just once.

However, there are special situations. Due to network or other failures, the client has to be able to retry sending messages, and the server has to implement an operation to be idempotent in order to process a particular message just once.

Message Publishing & Subscription

As a more flexible approach, you might also want to use a publish/subscribe mechanism so that your communication from the sender will be available to additional subscriber microservices or to external applications.

Your implementation will determine what protocol to use for event-driven, message-based communications. AMQP can help achieve reliable queued communication.