In a traditional enterprise application, all of the data that you need to complete a request is stored in a single database that has ACID properties (the term ACID stands for atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability). Therefore, you can guarantee consistency by using the transactional features of the relational database system.

End-to-end transactions in microservices

In microservices architectures, an end-to-end transaction might span multiple services. Each service might provide a specific capability and have its own independent database.

Two patterns that can be used to implement a transactional workflow in a microservices architecture.

- Choreography-based saga

- Synchronous orchestration

Example application:

Customers have a credit limit and the application must confirm that a new order will not exceed the customer’s credit limit.

The workflow is as follows:

- A client submits an order request that specifies a customer ID and a number of items.

- The

Orderservice assigns an order ID, and stores the order information in the database. The status of the order is marked aspending. - The

Customerservice increases the customer’s credit usage stored in the database according to the number of ordered items. (For example, an increase of 100 credits for a single item.) - If the total credit usage is lower than or equal to the predefined limit, the order is accepted and the

Orderservice changes the status of the order in the database toaccepted. - If the total credit usage is higher than the predefined limit, the

Orderservice changes the status of the order torejected. In this case, the credit usage is not increased.

Choreography-based saga

Architecture overview

In a choreography-based saga microservices pattern, microservices work as an autonomous-distributed system. When a service changes the status of its own entity, it publishes an event to notify other services of updates. The notification event triggers other services to act.

You use database to store events before publishing them. The Order and Customer services store events in the event database at first. Then, the stored events are published periodically using Scheduler.

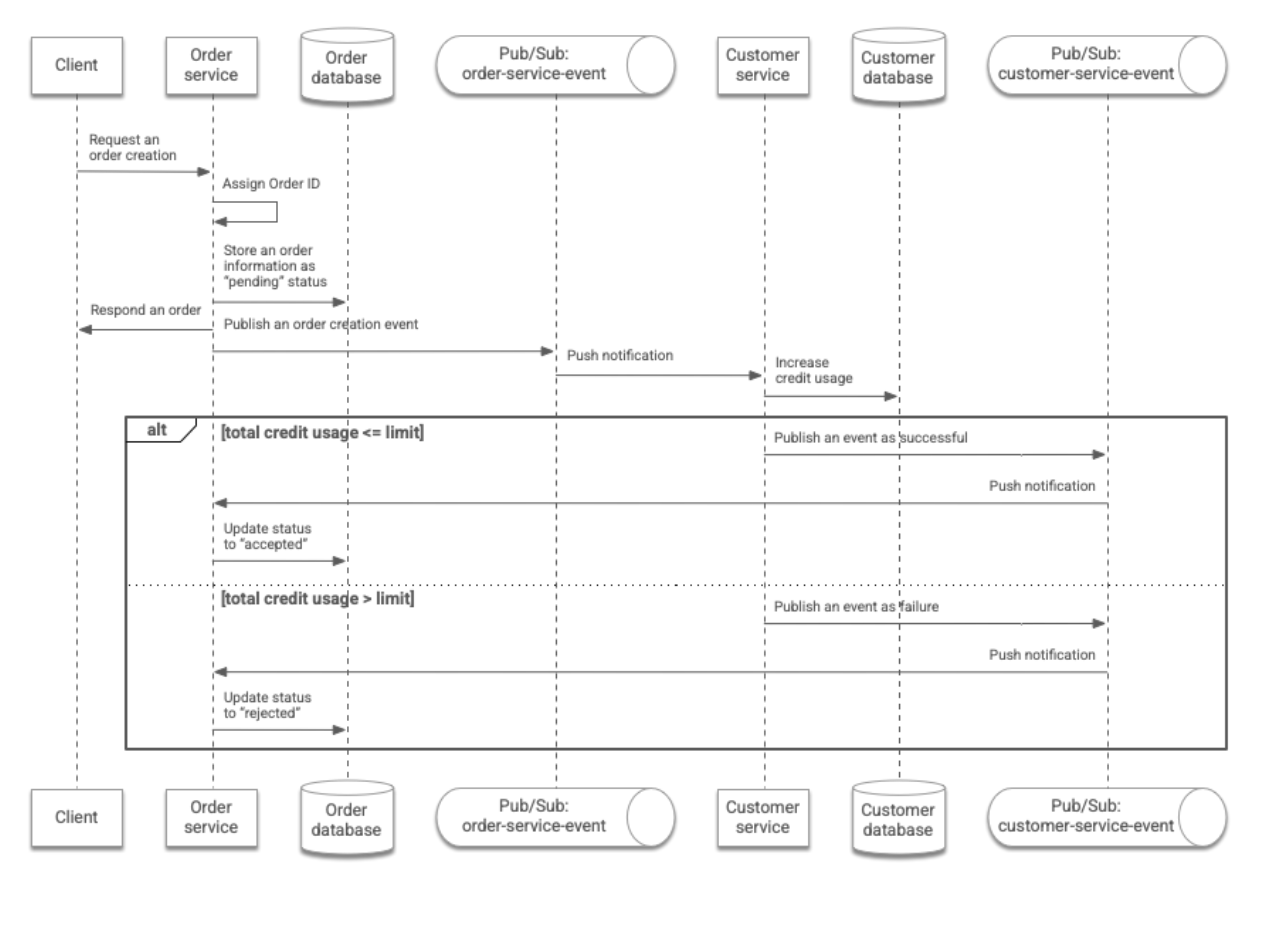

Transactional workflow

The event publishing process

When a microservice modifies its own data in the database and publishes an event to notify the database, these two operations must be conducted in an atomic way. For example, if the microservice fails after modifying data without publishing an event, the transactional process stops. In this case, the data can potentially be left in an inconsistent state across the multiple microservices that are involved in the transaction. To avoid this issue, in the example application used in this document, the microservices write event data in the backend database instead of directly publishing the events to Pub/Sub.

Data is modified and the associated event data is written in an atomic way, using the transactional feature of the backend database. This pattern, which is shown in the following image, is commonly called application events or “transactional outbox”.

As shown in the preceding image, initially, the published column in the event data is marked as False. Then, the event-publisher service periodically scans the database and publishes events where the published column is False. After successfully publishing an event, the event-publisher service changes the published column to True.

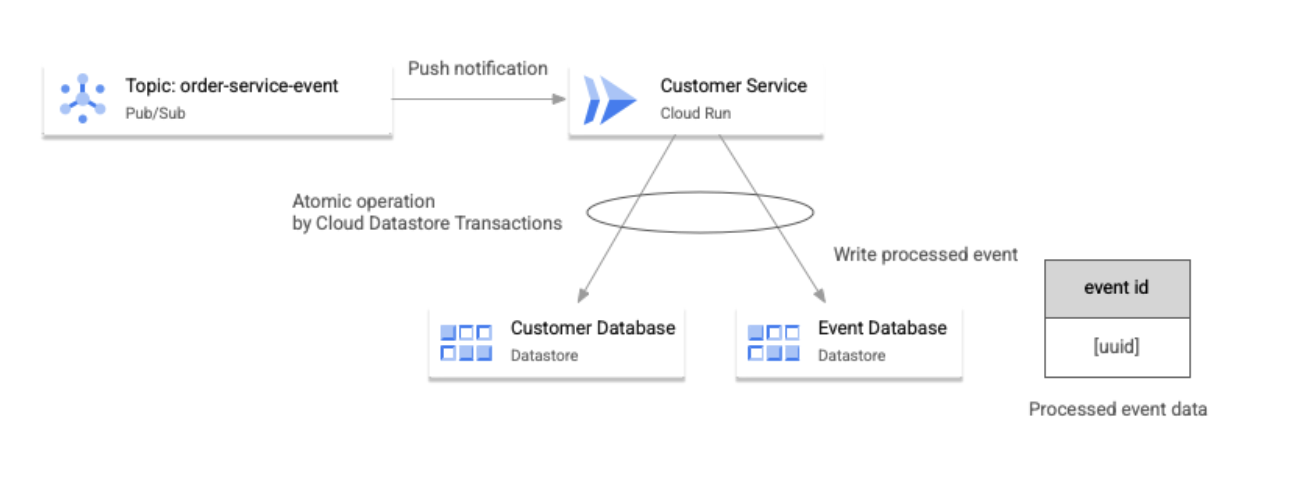

As shown in the following image, both the Order database and the Event database in the same namespace can be updated atomically by Datastore transactions.

If the event-publisher service fails after publishing an event without changing the published column, the service publishes the same event again after it recovers. Because the republication of the event causes a duplicate event, the microservices that receive the event must check for potential duplication and handle it accordingly. This approach helps to guarantee the idempotence of the event handling.

The following image shows how an example application deals with duplication of events.

The application handles duplicate events with the following workflow:

-

Each microservice updates its respective backend database based on the business logic triggered by an event, and writes the event ID to its database.

-

These two writes are conducted in an atomic way using the transactional feature that the backend databases use.

-

If the services receive a duplicate event, it’s detected when the services look up the event ID in their databases.

Handling duplicate events is a common practice when receiving events from Pub/Sub, because there is a small chance that Pub/Sub can cause duplicate message delivery.

However, accessing the database every time you process a message can cause performance issues. One solution is to utilize a database that has good performance and scalability—for example, Redis.

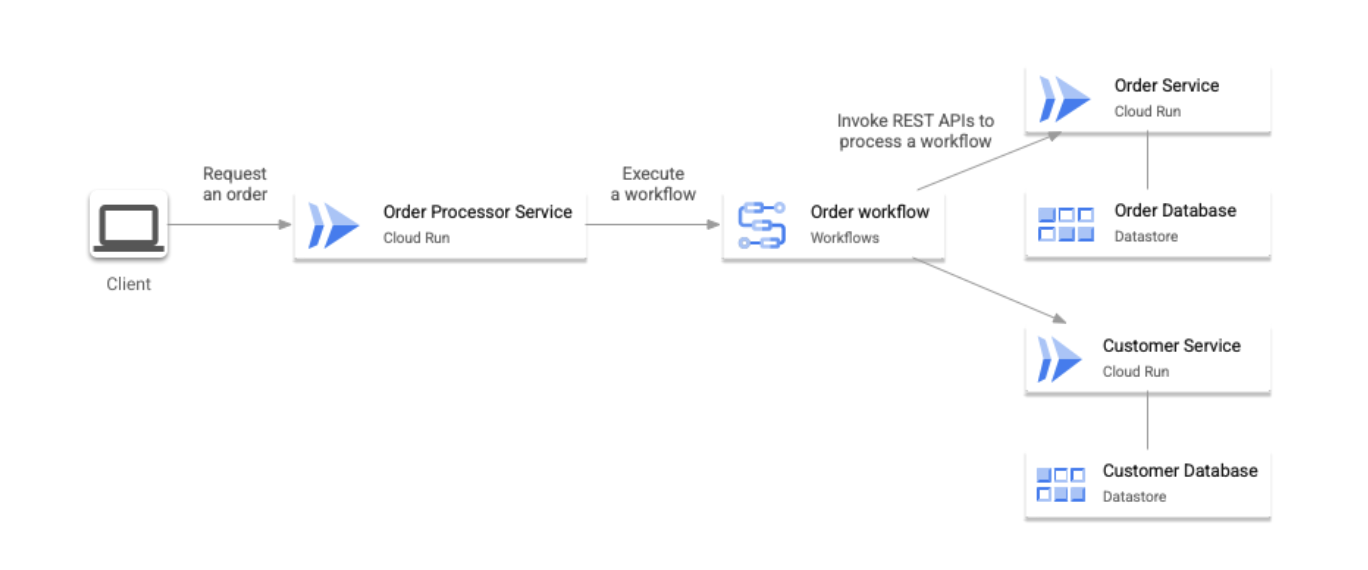

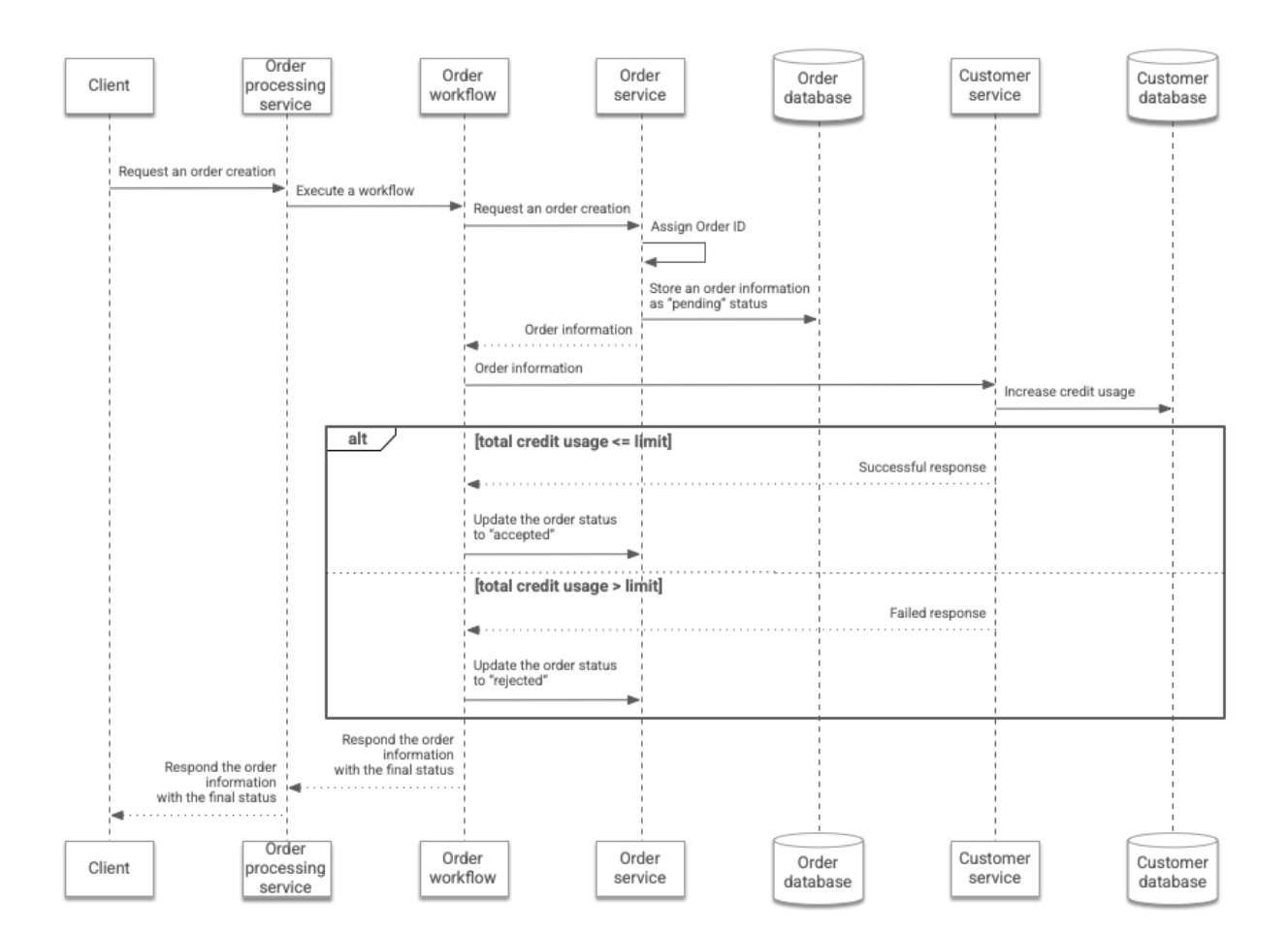

Synchronous orchestration

Architecture overview

In this pattern, a single orchestrator controls the execution flow of a transaction. The communication between microservices and the orchestrator is done synchronously through REST APIs.

Transactional workflow

Advantages and disadvantages

When you consider whether to implement a choreography-based saga or synchronous orchestration, the best choice for your organization is always the pattern which is most suitable for its needs. However, in general, because of the simplicity of its design, synchronous orchestration is often the first choice for many enterprises.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Choreography-based saga | Loose coupling: Each service publishes events to Datastore when there is a change in its own data. No information is sent to any other services. This approach makes each service more independent, and there’s a lower chance of the need to modify services when you introduce new services to the workflow. | Complex dependency: The implementation of the whole workflow is distributed among services. As a result, it can be complex to understand the workflow. This approach might accidentally introduce complexity into future design changes and troubleshooting. |

| Synchronous orchestration | Simple dependency: A single orchestrator controls the whole execution flow of a transaction. As a result, it’s simpler to understand how the transaction flow works. This pattern simplifies the modification of workflow and troubleshooting. | Risk of tight coupling: The central orchestrator depends on all of the services that make up the transactional workflow. As a result, when you modify one of these services or add new services to the workflow, you might need to modify the orchestrator accordingly. The extra effort required can outweigh the benefit of being able to modify and add services more independently to microservices architecture compared to monolithic systems. |

Reference

Transactional workflows in a microservices architecture on Google Cloud